Rapid GDP growth, due in part to high rates of investment and capital accumulation, has raised China out of poverty and into middle-income status. But progress in raising living standards has lagged, as a side-effect of policies favoring investment over consumption. At present, consumption per capita stands some 40 percent below what might be expected given China’s income level. We quantify China’s consumption prospects via the lens of the neoclassical growth model. We find that shifting the country’s production mix toward consumption would raise both current and future living standards, with the latter result owing to diminishing returns to capital accumulation. Chinese policy, however, appears to be moving in the opposite direction, to reemphasize investment-led growth.

Chinese Living Standards Lag Behind Income

China’s growth performance has been remarkable since the introduction of economic reforms in the late 1970s. According to the official data, real GDP growth has averaged 8.9 percent since 1978. That makes China the fastest growing economy over the period in a sample of 124 countries. (The sample includes all countries with GDP above $1 billion and populations above one million as of 2019.) To be sure, growth has slowed more recently, averaging 4.9 percent over the past five years. Even so, China’s performance remains exceptional, at just below the 90th percentile of our group.

Rapid economic growth has led to a similar increase in per capita income, lifting China into middle-income status. (Aside from net foreign investment income, GDP and economy-wide income are the same.) According to official figures, real per capita income has risen by a factor of more than thirty since 1978. Annual per capita income now stands at about $22,100 measured at purchasing power parity, in “2021 international dollars.” (Unless otherwise noted, real income figures rely on this measure throughout this post.) This places China at roughly the 60th percentile of the global income distribution.

Yet progress in raising living standards has lagged. Annual per capita household consumption now stands at about $8,300 measured at purchasing power parity, placing China at roughly the 45th percentile of the global distribution. Although the difference between the 60th and the 45th percentiles may not seem large, it translates into to a major shortfall in Chinese living standards. At the 60th percentile of the global distribution, consumption per capita would come to roughly $13,700, two-thirds higher than at present.

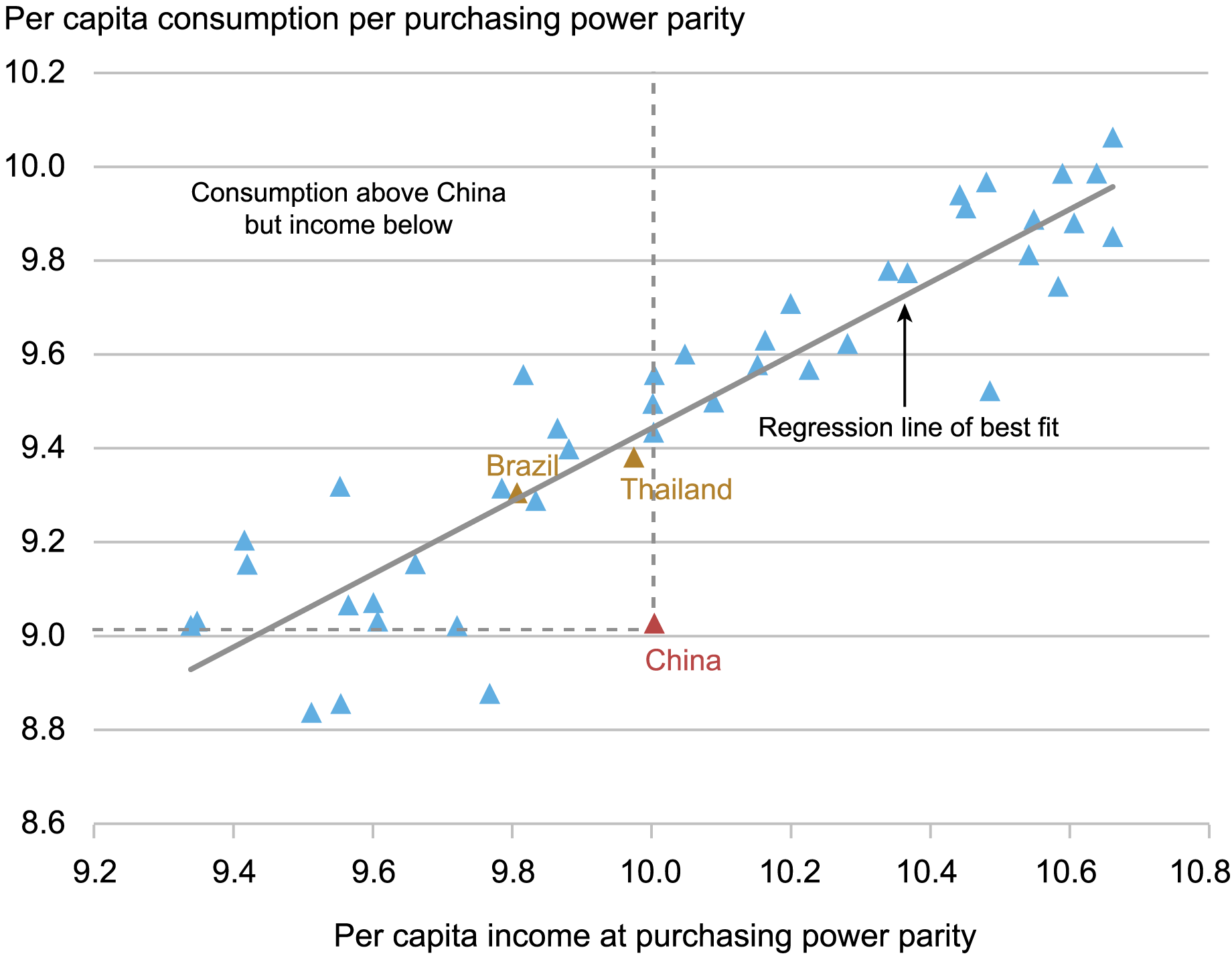

Focusing on consumption rather than income casts a new light on China’s development accomplishments. The point of economic growth, after all, is to raise people’s living standards, not to produce for production’s sake. But as shown in the chart below, eighteen of the forty-five middle income countries in our sample have higher average living standards than China but lower income levels. (Note that income and consumption figures are in natural logs, so that differences between countries translate roughly into percentages.) To take two notable examples, per capita consumption in Brazil is almost a third higher than in China with per capita income almost 20 percent lower; consumption in Thailand is 40 percent higher with incomes about 3 percent lower.

Chinese Consumption Spending is Unusually Low Given Income

Notes: Income and consumption figures are for 2023 and measured at 2021 purchasing power parities, with ICP data for 2021 are updated to 2023 using national real GDP, real consumption, and population growth rates. Middle income countries are defined as those with per capita incomes between one half and twice China’s level. Figures are in natural logarithms, giving differences a percentage interpretation: A difference of 0.1 (for example, between 9.4 and 9.5) is equivalent to 10 log percentage points and roughly 10 percent in arithmetic terms.

Our chart shows only private (or “household”) consumption, and goods and services provided by the government also contribute to living standards. But China does not rank any higher on broader measures of consumption that include government spending.

The source of China’s income-consumption mismatch is easy to locate. China devotes an extraordinarily high fraction of national income to investment rather than consumption. Investment as a share of GDP has been consistently above 40 percent since the mid-2000s and consistently above 35 percent since the mid-1980s. With the median global investment rate hovering in the mid to low 20s, China’s investment rates place it among the top 5 percent of countries worldwide every year since 1992.

Maintaining high investment to promote capital deepening is one key to development success. That entails sacrificing current consumption. But China’s lagging progress in raising living standards raises the question of whether it is on the wrong side of this trade-off. Would a shift to a lower investment path lead to higher living standards in future decades?

Lessons From the Neoclassical Growth Model

The standard neoclassical growth model provides a useful framework for analyzing the sources of Chinese growth. Under the model, economic growth comes from three basic sources: increases in capital inputs, increases in labor inputs, and improvements in technology. The growth contributions from capital and labor are equal to the growth rates of these inputs, weighted by their shares in the value of production. The growth contribution from technology (termed “total factor productivity” or TFP) is calculated as a residual, as the increase in output not explained by higher inputs.

China’s high investment share has supported a rapid buildup in the country’s capital stock. In fact, China’s capital-output ratio is now among the highest in the world in PPP terms. But capital accumulation is subject to diminishing returns: A given increment makes a smaller contribution to growth when capital is abundant than it does when capital is scarce. Moreover, as the capital stock rises relative to output, a higher fraction of new investment must go to offset ongoing depreciation.

The impact of diminishing returns is already in evidence. According to our estimates, increases in capital inputs now contribute less than 3 percentage points to annual GDP growth, down from a high of nearly 6 ppt. early in the last decade (see the chart below).

High Investment Spending is Delivering a Declining Growth Payoff

Contribution to Real GDP Growth from Capital Stock Growth

Notes: Real capital stock data through 2019 are taken from the Penn World Table. Thes PWT 2019 value is updated to 2023 using NBS real fixed investment data, via the perpetual inventory method. The growth contribution from capital accumulation is measured as the log growth rate of the capital stock multiplied by the capital share in national income.

Projection Results

We rely on the neoclassical model to study China’s income and consumption trajectory under two scenarios. The key projection assumptions are as follows.

- In the High Capex scenario, investment spending as a share of GDP remains at its current value through the projection horizon.

- In the Moderate Capex scenario, the investment share enters a gradual decline, stabilizing at 25 percent of GDP by 2040. The output no longer going to investment under the Moderate Capex scenario goes instead to support current consumption.

- Other factors affecting growth are kept the same across the two scenarios, including the paths of labor inputs, TFP growth, and relative prices.

Although these assumptions are debatable, the results should provide a useful benchmark as to whether high investment has turned self-defeating in welfare terms. This analysis builds on our earlier work: See Higgins (2020) and Clark and Higgins (2023) for implementation details.

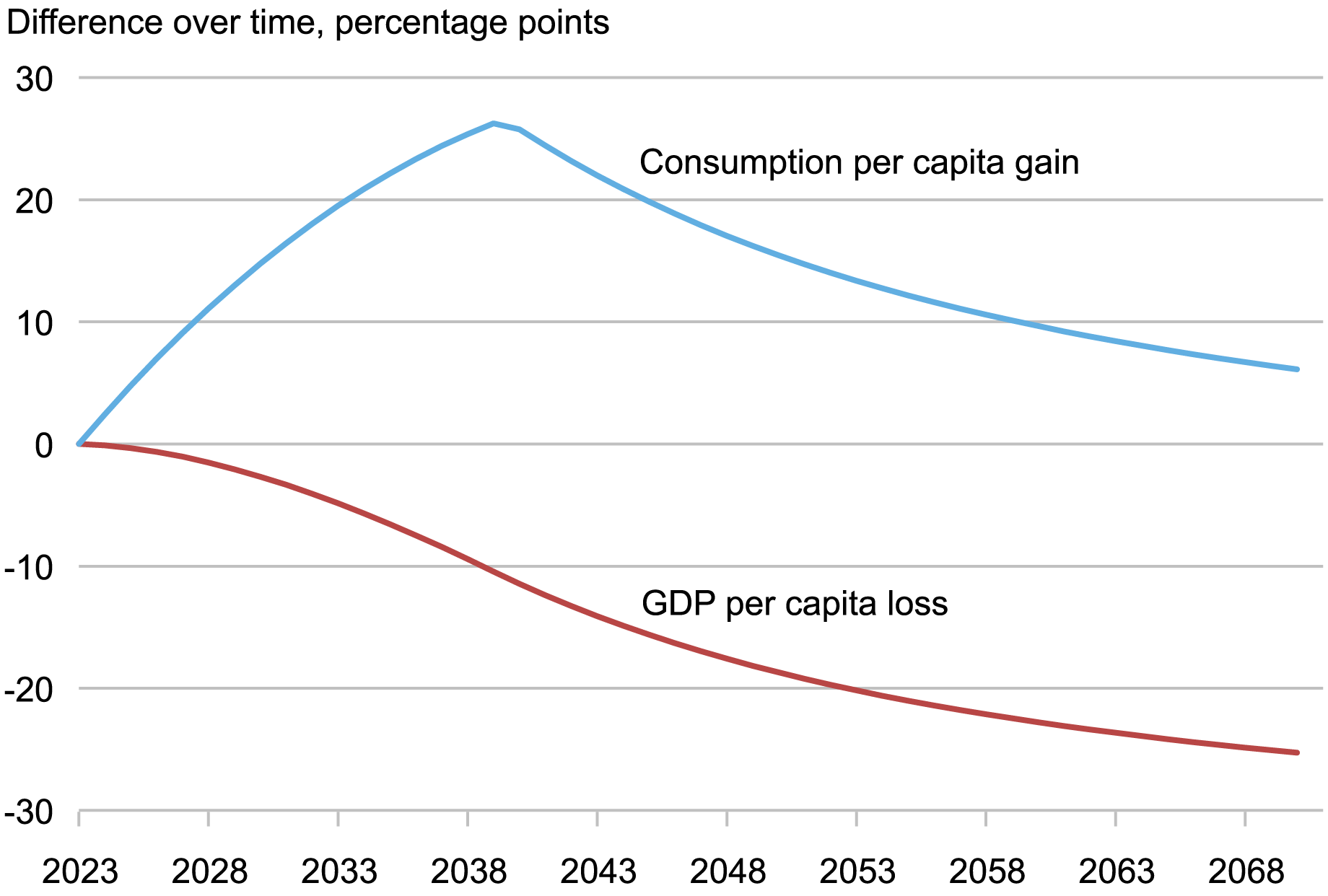

The projection results are summarized in the chart below. To highlight the impact of reducing capital expenditure as a share of GDP, the chart is expressed in percent differences. The red line shows the percent difference in real per capita GDP in the Moderate Capex vs. the High Capex scenario. The blue line shows the percent difference in real per capita consumption between these scenarios.

Lower Investment Would Mean Higher Chinese Living Standards

GDP and Consumption in Moderate vs. High Capex Scenario

Source: Author’s calculations. See Higgins (2020) and Higgins and Clark (2023) for implantation details.

Notes: Lines show the projected percent differences in real per capita GDP and real per capita consumption in the Moderate Capex vs. High Capex scenarios.

As can be seen from the red line, the Moderate Capex scenario puts GDP on a markedly lower growth path. By 2035, GDP is about 6½ percent lower than under the High Capex scenario. The GDP gap swells to 15 percent by 2045 and to about 25 percent by 2065. The source of this growth underperformance is straightforward. A lower investment share translates into slower growth in the capital stock, a smaller capital contribution to GDP growth, and a mounting GDP and income gap.

As evident from the blue line, however, the Moderate Capex scenario puts per capita consumption on a markedly higher growth path. By 2035, per capita consumption is almost 25 percent higher than under the High Capex scenario. This consumption advantage eventually fades given slower GDP and income growth. Yet consumption remains some 20 percent higher than under the High Capex scenario in 2045 and some 6 percent higher in 2070. Declining returns to capital accumulation mean that the MI consumption advantage would erode quite slowly over the more distant future. Indeed, extended projections don’t point to consumption convergence until after 2120.

Simple arithmetic helps explain why the Moderate Capex consumption advantage is so persistent. Under the scenario, the share of consumption in GDP rises to 55 percent of GDP from the current 39 percent—the flipside of the lower capex share. This boosts the level of consumption, given GDP, by a factor of roughly 1.4. GDP under a high-investment trajectory needs to be greater by a factor of more than 1.4 to offset this advantage. Given the neoclassical growth arithmetic, that’s not something that could happen anytime soon.

The precise numerical results of this projection exercise are less important than its central message. China is investing too much, trading large consumption gains over the next several decades for smaller gains in the distant future.

Notably, our analysis has focused on relative consumption levels, not on more abstract measures of social welfare. Formal welfare analyses typically apply a discount factor to future outcomes (for example, the risk-free interest rate). Such an approach would strengthen our results, attaching a low weight to consumption payoffs that materialize only in the 22nd century.

Back to the Future for Economic Policy

The notion that China should rebalance its economy away from investment spending and toward consumption amounts to familiar received wisdom in international policy circles. It is also the traditional official position of the Chinese government, adopted as a goal as long ago as the 2004 Central Economic Work Conference and reaffirmed in many subsequent documents. Nevertheless, the data indicate that little rebalancing has occurred in the two decades since.

As for the prospects for future rebalancing, President Xi’s public focus has been on industrial objectives, notably, the need to promote “new quality productive forces” in high-tech industries while maintaining a strong presence in traditional industries. The policy statement issued after the Communist Party’s July leadership meeting took a similar tack, featuring extensive discussion of investment and industrial policy but only a single passing reference to consumer spending. The shift in official rhetoric has been matched by a surge in bank lending to the industrial sector, a development highlighted in a Liberty Street Economics post a few months ago. To be sure, the authorities have introduced a variety of additional stimulus measures in recent weeks. But these seem more focused on stabilizing the investment-heavy real estate sector and local governments than on supporting consumption.

In short, China’s growth strategy appears to be reverting to the manufacturing- and investment-focused posture that prevailed in prior decades. Time will tell whether this “back to future” strategy can support sustained growth. But it will surely leave Chinese living standards lower than they could be.

Matthew Higgins is an economic research advisor in International Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Matthew Higgins, “Why Investment‑Led Growth Lowers Chinese Living Standards,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, November 14, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/11/why-investment-led-growth-lowers-chinese-living-standards/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).