This article is part of the US-China Dynamics series, edited by Muqtedar Khan, Jiwon Nam and Amara Galileo.

The rise of China is one of the most popular topics in the contemporary IR debate. Its rise will be felt in most of the regions of the world and will influence global development for the decades to come. The purpose of this article is to explore the U.S.-Iran-China relationship triangle in the context of the rising Chinese influence within the U.S.-dominated hierarchical international system. It will provide certain policy recommendations the U.S. should undertake to counter the Chinese challenge to its global leadership by viewing the particular problem through the Middle Eastern and, more specifically – the Persian Gulf and the Iranian angles. The overreaching argument is that the restoration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action provides the best bet America has for tackling the Chinese challenge to the U.S.-dominated global hierarchy. However, its full restoration in the initial form is unlikely. The scaled-down version of the JCPOA should be pursued instead.

The article is divided into two parts. In the first part, I begin with the two theoretical models utilized – 1) the multiple regional systems approach by Lemke and Werner (1996) and 2) imperial interpolarity by Nejad (2021). I then turn on to the overall description of the Chinese growing clout in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf sub-region before delving into the specific case of Iran. Within the case study, I put emphasis on the particular factors driving China-Iran cooperation and the domestic debates within the Iranian leadership circles on foreign policy vis-à-vis the U.S. and China. The second part focuses on the responses the U.S. should undertake regarding the problem highlighted in the first part. I begin with the overall American strategic considerations about the rise of China before highlighting their connection to the Middle East and Iran in particular. I then turn on to my central argument about the necessity to restore the JCPOA and the possible steps the U.S. could undertake to facilitate this matter.

Theoretical Models Used

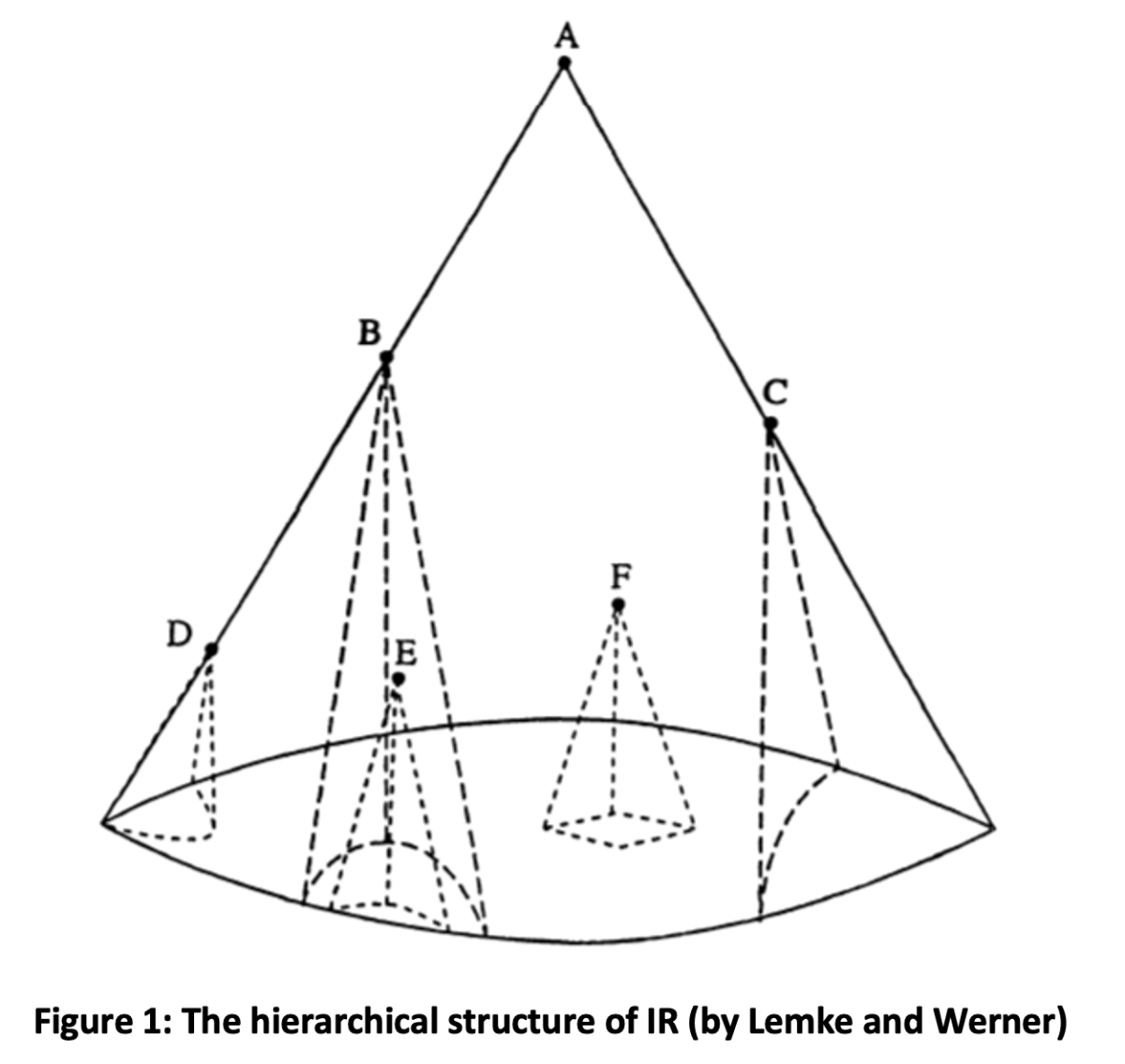

The arguments outlined in this policy paper are based on two theoretical models, which propose to view International Relations as a system of hierarchy. The first is the multiple regional systems approach by Lemke and Werner (1996) and the second is imperial interpolarity by Nejad (2021). Lemke and Werner believe that the global system of international politics consists of a set of multiple regional systems. Each of them has a separate set of countries fighting for local control. When this control is established, the country on the top of the regional system competes for control over the global system. It is also important that the countries on the higher hierarchical level (namely local leaders and the global leader) have the power to intervene in the lower-level hierarchies. Each of these local systems also has its set of local rules, norms, and procedures that govern international relations, which, together with the aforementioned power interactions, are embedded in the global system. For the graphical illustration of this model, see Figure 1.

I would argue that the Persian Gulf, where Iran is located, can be seen as one of these local hierarchies, which is a part of the wider Middle Eastern hierarchy (still doesn’t have a clearly defined leader) and a part of the U.S.-dominated global international system. The rules and norms of this region are clearly constructed with the U.S. global interests in mind – namely the dominance of Saudi Arabia. According to Gause III (2010), historically, the Persian Gulf has been a tripolar system of power (with Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq being the major powers and the small Gulf monarchies minor ones). However, the U.S. occupation of Iraq has put this country effectively out of the game. When it comes to Iran, the U.S. has applied heavy economic sanctions and utilized the policy of international isolation. This has made it effectively weakened and opened up the opportunity for Saudi Arabia to become the strongest player (local leader) in the region. Even though the relatively high degree of Iranian adaptability has made its preponderance with Saudi Arabia rather marginal, we can argue that Tehran has been forced into a subordinate position. Moreover, this position doesn’t allow it to benefit from the U.S.-led order.

The imperial interpolarity model by Ali Nejad is used as a complementary tool to Lemke’s and Werner’s model, as shown above. It helps to highlight the central problem of this paper – the rising influence of China in the Persian Gulf particularly in Iran. It adds the layer of specificity meant to characterize the phase between the fully established multipolar system and the U.S.-dominated unipolarity. Namely, by building upon the work of Giovanni Grevi, Nejad paints the picture of a world that is not purely dominated by the United States anymore. The U.S. still holds a preeminent place due to its major military power, enormous influence in the global financial system (which is tied to the capitalist system encompassing the majority of the globe), soft power tools, and the role as an educator of the large chunk of the global elite (Nejad, 2021). However, there are also other great powers emerging, which are both challenging the U.S. predominance and are also dependent on its led order for their economic growth.

Essentially, Nejad’s model can be used to characterize Lemke’s and Werner’s hierarchical system as being the one within the transition process. The power of the global leader (the United States) is waning and there is both increasing struggle for the position of a local leader within the specific hierarchies (e.g., Russia in the Post-Soviet space and China in East Asia) and often the steady growing presence of these would be local leaders outside their own regions (e.g. Russia in the Middle East and China in Africa). The latter is done with the aim of gradually reaching parity with the U.S.’s privilege of a global leader – namely, its ability to intervene in any region located within the particular hierarchy. If such a parity can be reached, the rising powers will have more levers of influence to challenge the existing power structure and facilitate its transformation from a hierarchical unipolarity to something more reminiscent of a balance of power multipolarity (essentially a transition process will be complete). The reason why the U.S. challengers are resorting to such a race of parity in terms of privileges instead of directly challenging it on a global level (e.g. by initiating a great power war) is connected both with the necessity to reduce a still notable power gap with the global leader, by achieving control over the local hierarchies first (where the U.S. supported clients are often dominating) and by unwillingness to overly destabilize the global U.S. dominated economic ties they are dependent on. Essentially, any direct conflict with the United States entails an unnecessary risk of significantly sapping the resources vital for the generation of power on the international stage.

China’s Growing Clout in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf Subregion

In such a context, the Middle East has felt an increasing Chinese presence. The region plays a significant role in its Belt and Road initiative, which plans to connect the Eurasian landmass with China through land and maritime trade routes (Chatzky and McBride, 2020). As Rezaei (2021) has noted, China is already the largest investor in the region and trading partner for 11 Middle Eastern countries. Beijing has funded the construction of ports and industrial parks in Egypt, Israel, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. In 2015, China also officially became the biggest global importer of crude oil, with almost half of its supply coming from the Middle East. Its activities are envisaged in two key strategic documents – the 2016 “Arab Policy Paper” and the 2015 “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”. Both of them focus on energy, infrastructure construction, trade, and investment but barely mention security and military cooperation (Lons, Fulton, Sun, and Al-Tamimi, 2019).

Although an increased military presence next to important strategic locations in the region is definitely an interest of China (as highlighted by the establishment of a military base in Djibouti), China has been cautious not to antagonize the strongest state in the international system (the U.S.), which can use its financial clout to sanction Chinese activities. The comparatively marginal Chinese military presence so far can also be explained by the effective U.S.-established security architecture, which is predisposed towards ensuring freedom of navigation and the provision of energy access – the two main elements connected to the Chinese strategic interest in the region. Essentially, China feels that there is already a safe enough environment to protect its assets and citizens, so there is no need to bear additional military costs for the rising clout. However, it has been noted that as the Chinese economic presence continues to grow, it will most likely be followed by an increased military presence as well (Lons, Fulton, Sun, and Al-Tamimi, 2019). The military presence is also a key tool for exercising the previously mentioned privilege of the global leader – intervening in other local hierarchies.

The primacy of energy and navigation interests has also determined China’s focus within the Middle East itself – the Persian Gulf subregion. When looking at the hierarchy of Beijing’s diplomatic relations in the region, we can see that the bulk of countries that have Comprehensive Strategic partnerships (the highest level of cooperation) with China are located in the aforementioned area.

Growing China-Iran ties

Within the Persian Gulf itself, China seeks to facilitate a multi-vector relationship-building approach. It has engaged significantly with the Gulf monarchies but, at the same time, utilized the economic and political isolation imposed by the U.S. to strike lucrative economic deals with Iran. As Nejad (2021) notes, European businesses had a significant stake in the Iranian economy, but the U.S. financial pressure has effectively forced them out. However, this then meant that Iran was effectively handed over to China on a silver plate. Its economic presence can now be witnessed everywhere – “from the construction of the Tehran metro to the exploration of Persian Gulf oil and gas fields. Moreover, since the start of the “nuclear crisis”, China has been given preferential rates for its imports of Iranian oil” (Nejad, 2021, p. 290). Notably, in March 2021 The Diplomat wrote that China’s purchases of Iranian oil climbed to record highs in 2021. Over the past 14 months from that date, Iran sent 17.8 million tonnes of crude oil to China (Albert, 2021).

Moreover, Green and Roth (2021) note that we can see a growing tendency in terms of China-Iran bilateral trade, as it has grown from approximately $5.6 billion in 2003 to nearly $51.8 billion in 2014. Interestingly, during his 2016 visit to Tehran, Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping announced Beijing’s goal to increase bilateral trade to $600 billion by 2026. The visit also saw the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Belt and Road Initiative cooperation for a list of select Chinese projects announced in Iran since the inception of the initiative (Green and Roth, 2021). However, it also seems that the development of bilateral trade relations has been slowed down due to the adoption of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) (which caused more players to enter the Iranian economy) and the subsequent withdrawal from it by the United States (which returned the financial pressure to players operating in the Iranian market). Namely, the bilateral trade in 2020 stood just at $14.9 billion (Green and Roth, 2021).

Similarly to bilateral trade, Chinese investment has also grown substantially. FDI stock increased by 541 percent from $468 million in 2004 to $3 billion in 2019, with investments concentrated primarily in the energy and raw material sectors (Green and Roth, 2021). Reportedly, within the Iran-China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement signed in 2021, together with deepening military cooperation and deepening trade relations, China has also pledged investments in Iran of around $400 billion over 25 years (Full text of Joint Statement on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, 2021). However, the success or failure in this dimension is tied to the future of the Iranian sanction regime. Currently, China is cautious to risk being embroiled in the web of the U.S. imposed constraints since it might backfire on it economically. This cautiousness might be enforced by the competitors of Iran – the Gulf monarchies, which can largely satisfy China’s energy and transportation needs without such a risk.

Speaking of the current Iran-China military ties, they largely follow the same logic. Although they have been steadily growing, China’s approach is largely connected to the concerns about the unnecessary provocation of the United States and the alienation of its other partners in the region. Namely – if it were to significantly increase its military ties with Iran, the Gulf monarchies could be more reluctant to increase their military and economic ties with China. That is why China and Iran maintain a longstanding defense relationship consisting of semiregular high-level exchanges, combined exercises, and port calls, but they don’t have a military alliance and there have been no indications that it might be established (Green and Roth, 2021).

Debates within Iran Regarding the Encroaching China

Although Iran gains significant benefits from Beijing, its leadership is not uniform when it comes to deciding what approach to undertake in order to manage relations with both the U.S. and China. Nejad (2021) identifies four strands of thought in the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic, which are often present within leadership circles. Two of them correspond to the regional dimension (The Middle East), but the other two correspond to a more global level and deal directly with Iran-U.S. bilateral relations.

On the regional level, there are defensive realists and offensive realists. The former agrees that the U.S. is facing a decline and is slowly giving way to the rising powers, but disagrees over the pace and the policy ramifications of the process. As the U.S. downfall is not imminent, Iran has to be cautious and manage its ties with the rising powers carefully. Essentially a détente with the U.S. within a particular hierarchy would be the best course of action. This is because the U.S. can easily damage such countries as Iran. However, the latter believes that the world is already multipolar and Iran should not shy in using this moment to help change the existing regional power structure in tandem with the other rising powers (Nejad, 2021).

On the global level, there are rejectionists and accommodationists. Rejectionists believe that in order to protect the Islamic Revolution, any accommodation with the U.S. should be refused. “Rather, they see permanent enmity towards and confrontation with the U.S. as the “Islamic Revolution” (Nejad, 2021, p. 208). On the other hand accommodationists view engagement with the U.S. as a precondition for the realization of Iranian goals of security and status. Seeing the U.S. as the globe’s unrivaled economic and political power, they believe that only productive interaction with it can help Iran prosper (Nejad, 2021).

After the previous Iranian election, the power is in the hands of more hard-line politicians, who would be relatively more willing to subscribe to the offensive realist approach and increasingly move away from the strong emphasis on the accommodationist approach eschewed by the administration of Hassan Rouhani. The now-deceased president of Iran – Ibrahim Raisi, has also embraced one of the traditional strands in the Iranian foreign policy – “Look to the East,” which directly corresponds to seeking an increase in political and economic ties with China. Notably, Raisi’s first foreign visit was to the capital of Tajikistan – Dushanbe for a summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Council (SCO). Within the event, he won Iran’s acceptance for full membership within the SCO – the regional security and political bloc dominated by Russia and China. Tehran views the joining to the organization as an important step for boosting defense and economic cooperation with both China and Russia (Yazdanshenas, 2021).

What Should Be the U.S. Response?

The overall strategic considerations vis-à-vis China

Before moving on to specific recommendations the United States should undertake within the U.S.-Iran-China triangle, its overall strategic considerations vis-à-vis China should be highlighted. Being the dominant power within the current imperial interpolar hierarchy, the United States is interested in retaining its position as long as possible. This means that it has to make sure that such rising powers as China do not challenge it through the great power war and also do not achieve parity in terms of being able to intervene in any region on earth.

It was already mentioned in the first chapter that China significantly benefits from the U.S.-led economic order and also has notable power preponderance over China (see, for example (Wohlforth, 1999). These two factors deter Beijing from challenging the U.S. militarily, so they should be kept intact.

Luckily for the U.S., its led economic order is relatively stable. I would argue that China (at least for now) does not really seek to overturn the preeminence of Washington in this sphere since even its so-called alternative institutions – Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Asian Development Bank, and The New Development Bank, albeit with some modifications largely reflect the existing U.S. established practices. Even more – even as China creates alternatives, it in parallel seeks to advance its interests within particular American-dominated structures – such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), International Telecommunications Union (ITU), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and others (Hillman, 2020).

The power preponderance dimension, however, is less stable. China’s possible domination over the East Asian local hierarchy can potentially reduce the existing power gap and thus make the war with the U.S. seem like a more attractive option. In this context, Beijing already applies significant pressure on the key American allies (Japan and South Korea), who are designed to both check one another and be local leaders in the U.S. name.

America, in such a context, needs to be able to demonstrate its commitment to its regional partners and signal that any significant attempts to change the regional Status Quo will be met with a large-scale conflict with the United States. Such a scenario with the current power distribution and economic dependence would mean the sure Chinese defeat. The best way how to signal this commitment is to increase the presence of military assets. However, as the U.S. military capabilities are not unlimited, these assets would most likely would have to be taken from other regions. Christensen (2001) notes that sometimes Chinese analysts emphasize political geography as an advantage that China has in settling problems such as Taiwan by force. Essentially, the United States, as a sole superpower, often finds its military assets down elsewhere. That is why one strategy for addressing the Taiwan problem would be to wait until the United States is politically and militarily distracted in another theatre.

The Middle East is definitely one such theater, and the United States has often expressed willingness to get out of the region and not be entangled in the security challenges stemming from this area. For example, many advisors close to President Biden have reported to the media that his administration is “extremely purposeful to not get dragged into the Middle East” (Bertrand and Seligman, 2021).

Additionally, the U.S. withdrawal from the Middle East (and particularly the Persian Gulf) can also hinder the third dimension of the Chinese challenge – achieving parity in terms of the ability to intervene in any region globally. At first glance, this might seem counterintuitive because it technically might improve the Chinese maneuverability in terms of increasing its own presence (including the military one). However, the decreasing U.S. clout also means the lessening ability of Beijing to free ride on the security architecture provided by Washington. In this sense – the increasing costs for protecting the economic interests might serve as a sort of hindrance to the Chinese plans in the Persian Gulf and the wider Middle East. Essentially, Beijing will have a harder time deciding whether it is ready to pay the higher cost for the attainment of the above-mentioned intervention privilege.

Even if China decides to pay the cost (which could be the case, taking into account the connectivity of the region to its interests in Central Asia), it might find it difficult to sustain its multi-vector relationship-building approach. For example, the Gulf states might react harshly towards increasing Chinese military ties to Iran, whereas Iran might condemn the significant growth of the Chinese Gulf military cooperation. Beijing might be inclined to choose its side, which would entail increased risks of friction.

However, in order to leave the Middle East, the U.S. has to make sure that its most vital interests for the maintenance of the military and economic hegemony in the region remain intact. That includes the stability of the Gulf monarchies, which leads to the uninterrupted supply of oil to the global markets and the free access to important geographical locations necessary to project military power and maintain the free flow of goods.

However, in order to successfully maintain the existing Status Quo, the United States needs to achieve stability in its relations with Iran. Unfortunately, it continues to resist the U.S. imposed Persian Gulf regional order (favoritism of the Gulf monarchies) through engaging in proxy wars in the wider MENA region and undertaking armament programs (especially the nuclear one). The Iranian revisionist foreign policy has alerted the U.S. allies in the Middle East – Saudi Arabia and Israel who are keeping the option of military action against Iran on the table. However, if such a scenario comes to fruition, the U.S. will definitely be forced to solve the issue at hand.

In such a context, dealing with Iran is vital before any reorientation can take place. In the following section, I will argue that the restoration of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is the best bet the United States has for achieving this goal. Additionally, it can provide certain side hindrances to China’s ability to achieve privilege parity in the Persian Gulf.

Why JCPOA?

Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or informally – the Iran nuclear deal is one of the hallmark achievements of U.S. diplomacy vis-à-vis Iran. Concluded by President Barack Obama, it addresses the key issue that might create new, U.S. attention-demanding conflict in the Persian Gulf. Namely – the nuclear armament of Iran. Under this deal, the U.S. agreed to lift its economic sanctions in exchange for the Iranian commitment to curb its nuclear capabilities.

The agreement was signed with the correct calculation that nuclear-armed Iran can be a threat to the global non-proliferation regime and, even more specifically – cause Israeli and/or Saudi intervention (which would likely ask for American support). Both of these scenarios would significantly hamper the U.S. disengagement from the region, so the nuclear issue had to be solved.

Unfortunately, in 2018, President Donald Trump decided to leave the agreement, because it didn’t address the other two key issues of concern to the U.S. and its regional allies – the growing regional influence (both within the local Persian Gulf hierarchy and the wider Middle Eastern hierarchy) and several other armament programs (e.g. the ballistic missile ones). The policy of “maximum pressure” was implemented, which restored both the previously imposed sanctions and adopted the new ones. However, despite causing significant episodes of regional upheaval, it failed to both alter the Iranian behavior and convince it to renegotiate the JCPOA. After Trump’s loss in the 2021 election, President Joe Biden has been engaged in multilateral negotiations in Vienna in order to attempt the restoration of the deal. However, the negotiations have been very cumbersome and have often reached an impasse over key issues (Erlanger, 2021).

Nevertheless, the restoration of the JCPOA is vitally important. The agreement provides the only meaningful mechanism which could potentially allow to avert additional Iranian pressure while the additional presence in East Asia is being built. In addition to taking away a major incentive for Israel and Saudi Arabia to engage in a new regional conflict, JCPOA also gives Iran important access to the U.S.-dominated global economic order. Similarly, as in the case of China, the economic benefits it can bring can reduce the willingness to seek conflict with America.

Moreover, although Iran has signaled that it will not bow to pressure and extend the JCPOA framework to the issues of regional influence, the nuclear deal can still provide a good impulse for convincing the key regional players to engage in deconfliction endeavors. It is important to note that soon after Biden’s victory and the declaration of his willingness to return to the JCPOA, Saudi Arabia started a dialogue with Iran in Baghdad to ease mutual tensions. International Crisis Group (2021) notes that this was due to Saudi belief that the issues of regional power projection and ballistic missile program would end up falling by the wayside among all the other issues that have to be discussed with Iran within the JCPOA framework. Iran, however, was interested in improving its regional standing and also fulfilling its stated policy of opposing the demand for non-nuclear issues to be included in the discussions on the nuclear agreement. Essentially, Iran could highlight that these issues should be confined exclusively to the regional players (Guzansky and Shine, 2021).

When it comes to raising the costs for increasing Chinese clout and thus its ability to achieve intervention privilege parity with the U.S. in the Persian Gulf, it is necessary to understand that Western economic actors are still interested in entering this lucrative market. The removal of the threat of international sanctions through the adoption of the JCPOA could again provide an important platform for Western businesses to enter and successfully compete with the Chinese established presence. Beijing can, of course, also utilize the economic opportunities opened by the JCPOA, but the competition might definitely be stiffer.

The successful operation within Iran by the Western businesses and the economic benefits it might bring to the clerical regime could also serve as an important tool for giving additional ammunition for the Iranian decision-makers more inclined to cooperate with the United States (essentially, defensive realists and accommodationists). Although the current administration has undertaken the “Look to the East” policy, their approach could still possibly be moderated by internal voices highlighting the benefits Iran has from its “Look to the West”. However, for these voices to have at least a moderate chance of success, they would need to demonstrate the tangible gains that the fully functioning JCPOA is built to bring.

How to restore the JCPOA?

The main problem regarding the restoration of the JCPOA is the willingness of both the U.S. and the Iranian side to expand its original format (essentially constructing something similar to the JCPOA+) and the lack of trust. The discussions on the future of the nuclear deal have covered such key topics as the possibility for Iran to engage in follow-on negotiations that would encompass its regional power projection capabilities, the length of Iranian “breakout time”, guarantees that the U.S. will not withdraw from the deal in the future, designation of the International Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organization and the willingness of Iran to see sanction removal before returning to full compliance. Even more – Iran also wishes to see the sanctions removed that were imposed by the U.S. outside the original JCPOA framework.

In all of these issues, both sides have been surprisingly inflexible, which has often raised doubts about the possibility of saving the JCPOA from utter collapse. Even though this scenario has been averted thus far, the window of opportunity has almost completely closed. This is evidenced by the indication that America is willing to use “other options” if talks fail and Iran becoming a near-nuclear-threshold state (e.g., see Sanger, Barnes, and Bergman (2022) and Middle East Eye (2021)).

Before the window has closed completely, the United States should recognize that it is close to impossible to change the Iranian negotiating position and tailor it to U.S. interests. This is both because Washington has demonstrated itself as an unreliable international partner that can’t be trusted and because there are divisions within Iran on whether the JCPOA should be restored at all. For example, Eric Brewers of the Center for Strategic and International Studies has noted that the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal has empowered voices within Iran who believe that in 2015, they gave away too much and demanded too little (Jewish Council for Public Affairs, 2021).

The most optimal scenario in such a situation would be to bite the bullet and understand that the odds of achieving the JCPOA+ or even the JCPOA in its original form is unrealistic. Instead, the focus should be on something similar to the mini-JCPOA, which would tackle the most pressing aspects of the nuclear program (such as freezing the Iranian enrichment efforts). This format should then be used as a springboard for further negotiations, which would aim to reach a more comprehensive deal. Additionally, the U.S. should do everything that’s possible to keep the ongoing dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia alive. For example, it could involve the UN building a new regional security initiative with the participation of Israel, Iran, Iraq, and the Gulf states. Such a move would help to uphold the momentum for the continuation of international talks with Iran and would also help to achieve one of the U.S. key interests – putting its regional role “into the box”.

Additionally, the U.S. should engage in a comprehensive dialogue with Israel and, to some extent, also the Gulf states to assuage their fears that Washington will not seek to make such an arrangement as a permanent one. Their acceptance is vital because there is always a certain risk that either of these actors (especially Israel) might act without U.S. authorization. Finally, the U.S. should also engage with Iran itself (perhaps by frontloading some removal of sanctions as a sweetener) and convince it that such a scenario is the best way forward in the current situation. Iran could gain certain economic benefits (vital for its battered economy) and, more importantly – wouldn’t close its doors to the West and would keep the possibility of a comprehensive deal open. In a sense – the possibility of a regional conflict, which can also pose significant risks to Iranian security, would be reduced. In this context, the possible cooperation with China to pressure Iran to continue dialogue can also be explored (since it continues to buy Iranian oil and does not want to see increasing destabilization in the Persian Gulf), but it is not very likely, since it would mean easing the American reorientation to East Asia (higher strategic priority for China).

Conclusion

This paper has sought to highlight the existing Chinese power transition of the global hierarchical system within the U.S.-Iran-China triangle. By looking at the current dynamic of the increasing Chinese presence in Iran, I have argued that in the context of U.S.-Iran-China relations, the restoration of the JCPOA provides the best bet America has for tackling the Chinese challenge for the U.S.-dominated global hierarchy. Namely – the existence of the JCPOA would help to tackle the Chinese aspirations to reduce the preponderance with the U.S. through the domination of East Asia and also increase the costs, risks of friction, and internal Iranian resistance to the Chinese willingness to achieve parity of intervention privilege.

However, due to the unwillingness of both the U.S. and the Iranian sides to return to the original framework of the JCPOA, but rather expand it, its restoration in the initial form is unlikely. The best bet would be to focus on something reminiscent of mini-JCPOA, which would tackle the most pressing aspects of the Iranian nuclear program and would provide at least some sanctions relief. The U.S. should then capitalize on this smaller version of the deal to engage in a more comprehensive dialogue while engaging in talks with its regional allies and supporting the existing Saudi-Iranian bilateral negotiations track. Simultaneously, some form of coordination with China can be explored. These actions definitely won’t pull the JCPOA out of its life support stage, but they can at least provide some momentum to keep the dialogue going.

Notes

References

Albert, E., 2021. China Is Buying Record Amounts of Iranian Oil. [online] The Diplomat. Available at:

Al-Tamimi, N., Fulton, J., Sun, D. and Lons, C., 2019. China’s great game in the Middle East. [online] European Council on Foreign Relations. Available at:

Bertrand, N. and Seligman, L., 2021. Biden deprioritizes the Middle East. [online] POLITICO. Available at:

Chatzky, A. and McBride, J., 2020. China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative. [online] Council on Foreign Relations. Available at:

Christensen, T., 2001. Posing Problems Without Catching Up: China’s Rise and Challenges for U.S. Security Policy. International Security, 25(4), pp.5-40.

Erlanger, S., 2021. Iran Nuclear Talks Head for Collapse Unless Tehran Shifts, Europeans Say. [online] The New York Times. Available at:

Fathollah-Nejad, A., 2021. Iran in an Emerging New World Order. 1st ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

Fulton, J., 2019. China’s changing role in the Middle East. [online] Atlantic Council. Available at:

Green, W. and Roth, T., 2021. China-Iran Relations: A Limited but Enduring Strategic Partnership. Washington D.C.: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Gregory Gause, III, F., 2010. The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guzansky, Y. and Shine, S., 2021. Saudi-Iranian Dialogue: Toward a Strategic Change?. [online] The Institute for National Security Studies. Available at:

Hilman, J., 2020. A ‘China Model?’ Beijing’s Promotion of Alternative Global Norms and Standards. [online] Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at:

International Crisis Group. 2021. A Time for Talks: Toward Dialogue between the Gulf Arab States and Iran. [online] Available at:

Jewish Council for Public Affairs, 2021. Returning to the Iran Nuclear Talks: Understanding the Current Dilemma. Available at:

Lemke, D. and Werner, S., 1996. Power Parity, Commitment to Change, and War. International Studies Quarterly, 40(2), p.235.

Lons, C., Fulton, J., Sun, D. and Al-Tamimi, N., 2019. China’s great game in the Middle East. [online] European Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: https://ecfr.eu/publication/china_great_game_middle_east/

Middle East Eye. 2021. Iran nuclear deal: US preparing ‘alternatives’ if talks fail as Tehran criticises western powers. [online] Available at:

Rezaei, M., 2021. The Barriers to China-Iran Military Diplomacy. [online] The Diplomat. Available at:

Sanger, D., Barnes, J. and Bergman, R., 2022. Fears Grow Over Iran’s Nuclear Program as Tehran Digs a New Tunnel Network. [online] The New York Times. Available at:

Nasr, V., 2021. How to Save the Iran Nuclear Deal. [online] Foreign Affairs. Available at:

Further Reading on E-International Relations