For more than five decades, the Clean Air Act has prevented millions of premature deaths, hospitalizations, and lost work and school days. By one official reckoning in 2011, the act’s limits on harmful pollution has benefited the U.S. economy to the tune of $2 trillion by 2020, in contrast with $65 billion in costs to implement regulations.

But now the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is abruptly changing how it enforces at least parts of the Clean Air Act by not calculating the economic benefits of some regulations. The seemingly inevitable result is that Americans will soon breathe noticeably dirtier air and see worse health outcomes, experts say.

“I don’t think anyone wants to go back to … not being able to see anything,” says Camille Pannu, an environmental law expert at Columbia University.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The EPA will no longer consider the dollar value of lives saved or other ill effects averted by placing limits on fine particulate matter with the designation PM2.5 or ozone emissions in at least some cases, the New York Times reported on Monday. Instead the agency will only calculate the cost to industry to enforce the act’s rules.

To get a sense of why this matters, it is important to understand what ozone and PM2.5 do to our body. PM2.5 describes particles that have a diameter smaller than 2.5 microns. They are tiny enough to enter the bloodstream, lodge deeply in the lungs and cross the blood-brain barrier. PM2.5 has been liked to diabetes, obesity, dementia, cancer, low birth weight and asthma. Ozone, a key ingredient of smog, is particularly dangerous for people with asthma and other lung diseases, especially children.

The Clean Air Act was enacted precisely because the health effects of bad air are population-wide and difficult to evaluate. In other words, without estimating costs, even imperfectly, “everything is costly, and nothing is worth regulating,” Pannu says.

In a document reviewed by the New York Times, an EPA official cited language that argued that how the dollar value of the benefits of the regulation was calculated “provided the public with false precision and confidence.” Yet experts point out that that is part of the point: the act’s authors “wanted to have EPA regulate even if the science was uncertain,” says Lisa Heinzerling, an environmental law expert at Georgetown University.

Different presidential administrations have taken distinct approaches to totaling up the value of those benefits, but the science underlying these estimates is well established.

For decades, researchers have compared places with higher and lower levels of pollutants and have looked at differences in premature deaths and other negative health outcomes while controlling for other factors that could affect those numbers. Those analyses are then combined with economic studies that estimate the “value of a statistical life” by looking at, for example, the amount of lost wages incurred when a parent stays home with a child who is experiencing an asthma attack. Because this work has been going on for so long, it means researchers can feel confident in the value they arrive at, says Rachel Rothschild, an environmental law expert at the University of Michigan.

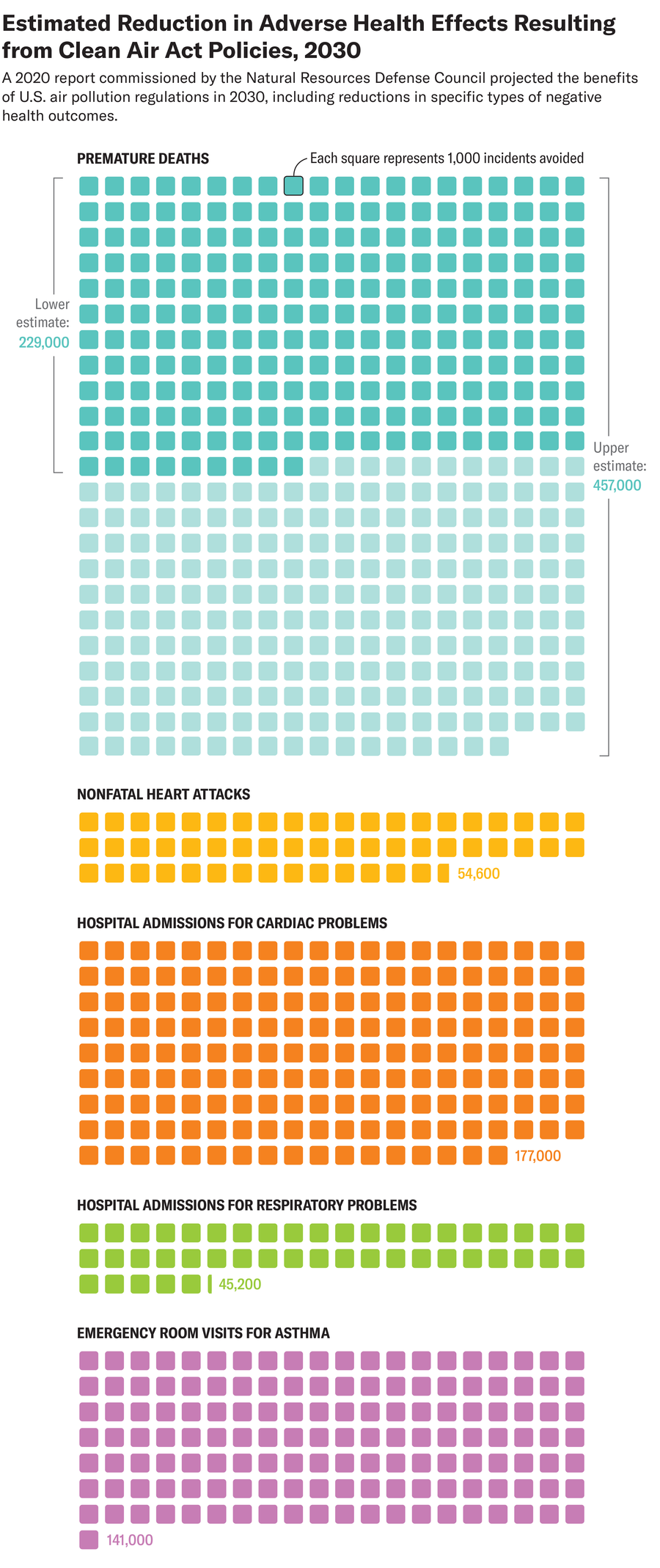

Amanda Montañez; Source: The Benefits and Costs of U.S. Air Pollution Regulations. Prepared by Jason Price et al. for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Industrial Economics, May 2020 (data)

Independent analyses have also been conducted that showed PM2.5’s “harms were so significant” and “the benefits [of the Clean Air Act] were so enormous” that they far outweighed the costs of implementing the law, Rothschild says. The Clean Air Act’s regulations “pay for themselves; they pay for the entire EPA,” Heinzerling agrees.

A 2016 analysis from the University of Chicago found that people in the U.S. had gained 336 million life-years, a measure of how long people are expected to live in a healthy condition, since amendments to the Clean Air Act were passed in 1970. And in 2011 the EPA estimated that updates to the act made in 1990 would prevent more than 230,000 early deaths, 75,000 cases of bronchitis, 120,000 emergency room visits and 17 million lost workdays by 2020. About 85 percent of these benefits stem from deaths avoided because of reductions in particular matter alone.

Estimates of cost are also inherently uncertain. And according to Rothschild, past EPA analyses have almost always found the agency overestimated those costs. She and others expect this move to be challenged in court.

It is also unclear how widely this new policy may be applied. Documents cited by the New York Times’ reporting suggest it will apply to proposals from the agency’s Office of Air and Radiation, with the consequences including repeals of limits on greenhouse gas emissions. The Times also cited similar language to what the EPA emails mentioned in a regulatory impact analysis posted on Monday concerning limits on nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide from combustion turbines at gas-burning power plants. Such plants are in demand at data centers to fuel their considerable power needs.

The EPA is legally required to provide its rationale and any data it is relying on to make such decisions, Heinzerling says.

In a statement in response to detailed questions from Scientific American, an EPA spokesperson said the agency is continuing to consider the impacts of PM2.5 and ozone on human health, adding that “the agency will not be monetizing the impacts at this time.”

“EPA is fully committed to its core mission of protect human health and the environment,” the statement continued.

The EPA spokesperson also noted that the previous Biden administration did not calculate the value of health benefits for some rules under the Clean Air Act, including for PM2.5. Rothschild says that some past administrations may have not quantified the benefits of every proposed regulation—particularly those that were very difficult to calculate. But, she says, “the health benefits from reducing particulate matter and ozone are some of the easiest to quantify and monetize out of all types of environmental pollution.”

“It’s disappointing that the EPA isn’t interested in making the best decision for the public,” Rothschild says.