A strand of the literature on de facto states emphasizes that de facto states’ foreign policy aims to ensure both physical security and recognition (Berg & Vits, 2018). Berg and Vits argue that de facto states look for protection from external patrons to maintain themselves and show the international community their capacity to do so (Ibid.). This paper states that instead of being solely driven by physical security concerns, bilateral relationships between de facto states are motivated by their quest for ontological security as they increase it through narratives. While existing literature emphasizes physical security as a key driver of de facto states’ foreign policy, this paper offers an alternative explanation. Bilateral ties among de facto states can be driven more by identity needs than strategic or physical security benefits. It departs from traditional accounts prioritizing physical security in de facto states’ foreign policy by demonstrating how identity-affirming relationships with similarly unrecognized entities, like Somaliland, serve Taiwan’s ontological security needs.

Drawing upon Mitzen’s (2006) accounts of ontological security, which distinguishes between physical and ontological security, this paper aims to explain what pushes de facto states to enter into relations with one another despite limited capacity to guarantee security. Here, we do not mean to assert that de facto states are acting «as a unified front against the restricting international legal order» (Ibid, p.2) but to look at the reasons for de facto states to enter into relations with their kin that seem less able to guarantee physical security than recognized states can. We will be looking at the relationship between Taiwan and Somaliland from the former’s point of view. This raises the following question: Why do de facto states, despite their limited capacity to provide physical security, pursue bilateral relations? We expect to find that relations between de facto states can be explained by an ontological security-seeking behavior, which aims at confirming their national identity and gaining recognition (Grzybowski, 2021) through narratives. For that matter, we will be analyzing Taiwanese narratives focused on their relationship with Somaliland. It is worth mentioning that here, Somaliland is understood as a context, as the other party in the bilateral relationship with Taiwan, rather than a case in itself. In fact, we will not be looking at Somaliland’s narratives on its bilateral relationship with Taiwan.

Defining de facto states in the absence of academic consensus

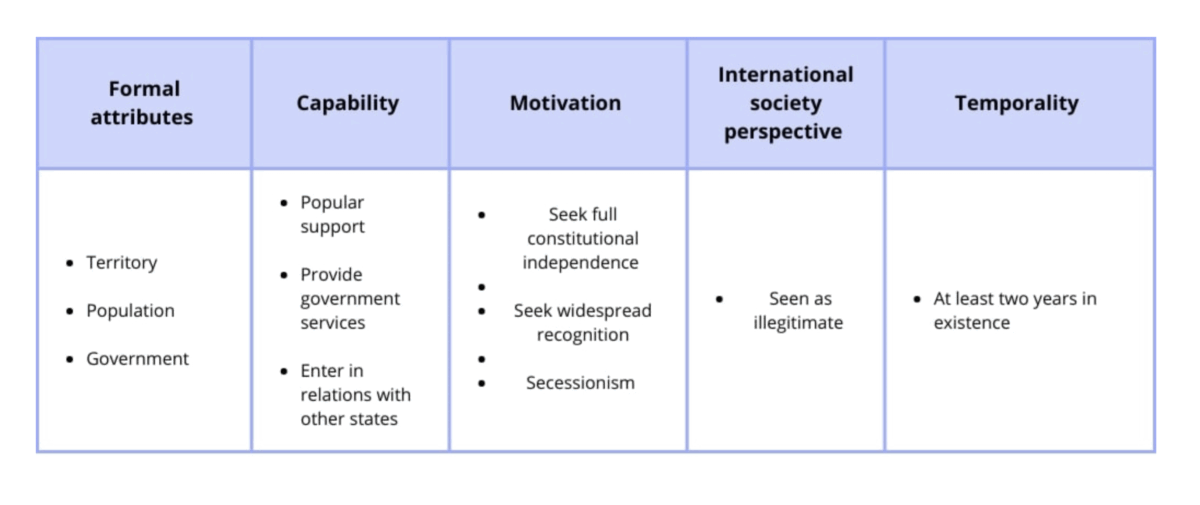

States benefiting from widespread recognition are often used as the main reference unit in international relations and security studies. This paper utilizes the concept of de facto states as its object of study, and we must specify what this term means before starting our research. The field of research on de facto states remains divided on the question of defining de facto states, and no consensus has been reached yet (Kosienkowski, 2022). These definitions usually differ in the criteria they use, which either reduce or increase the number of studied cases. As the aim of this study is not to take part in this definitional debate, we are obliged to specify our chosen definition, as it shapes the case selection process. Scott Pegg et al. (1998) consider de facto states as secessionist entities that combine the following characteristics:

«organized political leadership which has risen to power through some degree of indigenous capability; receives popular support; and has achieved sufficient capacity to provide governmental services to a given population in a defined territorial area, over which effective control is maintained for an extended period of time.» (Ibid., p. 1).1

These entities also share an inability to gain widespread recognition (Ibid). When comparing different definitions of de facto states, Kursani (2020) detailed what criteria arise from Pegg’s definition. He arranged them in five broader categories: formal attributes, capability, motivation, international society perspective, and temporality (Ibid.). We summarized these criteria in Table 1 in the Figures and Tables section, based on these five categories.

De facto statehood and foreign policy

Scholars such as Ker-Lindsay point out that de facto states also share stigmatization from the international community due to widespread nonrecognition by other states (Ker-Lindsay, 2018). This concept is useful for drawing the contours of de facto states’ foreign policy. Despite fulfilling statehood criteria as defined in the Montevideo Convention (Toomla, 2016), de facto states are treated as illegal entities, which drastically reduces their possibilities to maneuver in the international system in comparison to recognized states (Ker-Lindsay, 2018). In fact, scholars such as Visoka (2021) point out the crucial benefits provided by widespread recognition and show that these entities do not benefit from any protection by international law, cannot seek membership in multilateral organizations, or develop classical diplomatic and economic relations. In this sense, de facto states are stigmatized, as they do not benefit from these advantages, seeing their foreign policy options reduced.

According to Berg and Vits (2018), de facto states’ foreign policy is mainly aimed at ensuring physical security (added to recognition) and can be assimilated to small states in the way they can behave in that matter. De facto states can look for protection from external patrons to maintain themselves and show the international community that they have the capacity to do so (Ibid.). If such patron-client relationships do not exclude the possibility of a de facto state agency, they do limit their independence (Werner Bastek, 2019). Another way for de facto states to interact with the external world is to benefit from engagement without recognition. This concept encompasses a large range of interactions between de facto states and recognized states or international organizations (Caspersen, 2018), which do not result in recognition. According to scholars such as Caspersen, these interactions can take the form of «humanitarian aid, travel, educational exchanges, trade, and even some diplomatic links» (Ibid., p.4). Moreover, Florea (2017) highlighted that among three other factors, the survival of a de facto state is explained by patron-client relations with other recognized states. In this sense, one would agree that looking for support from similar entities that also suffer from smallness and stigmatization is not the best option to maintain the status quo of their existence.

Drawing from the above-listed options that de facto states have to enter into external relations, we can conceptualize our phenomenon of interest. In this study, the term “relations between de facto states” is understood in the following way: it encompasses any bilateral interaction between de facto states (based on the above-mentioned definition). These interactions encompass the same wide range of forms as engagement without recognition does. However, the concept of engagement without recognition accounts for interactions between a state and a given de facto state or the larger international community.

Ontological security and de facto states

Stability and routines

This study is embedded in a constructivist understanding of international security and uses the ontological security approach as its main theoretical base, which emphasizes the importance of identity, continuity, and stable relationships in enabling state agency. According to Eberle and Handl (2018), this framework is well-adapted to give explanations for foreign policy continuities, and this explains our choice. Our theoretical framework will mainly be grounded on Jennifer Mitzen’s work on ontological security. The idea that states do not exclusively seek physical security but also ontological security is one of the central premises of this theoretical approach (Mitzen, 2006). Mitzen defines ontological security as follows: «the need to experience oneself as a whole, continuous person in time—as being rather than constantly changing—in order to realize a sense of agency» (Ibid. p. 342).

In addition to physical security, this means, for states, that security also involves preserving their identity and their routines, which provide a sense of predictability and control (Ibid). According to Mitzen, states are facing existential, rather than physical, uncertainty, and this undermines their agency, which requires a stable environment (Ibid.).

Mitzen shows that ontological security is maintained through “routinizing relationships with significant others” (Ibid., p. 342). These routinized relationships provide “confident expectations, even if probabilistic, about the means–end relationships that govern [the actor’s] social life” (Ibid., p. 345). In essence, they structure how the state interprets the world and defines its role within it. This “basic trust system” (Ibid., p. 361) allows actors to focus on long-term goals by overcoming doubts and complexity:

“Because actors cannot respond to all dangers at once, the capacity for agency depends on this system, which takes most questions off the table” (Ibid., p. 346).

Mitzen also came up with the concept of ontological insecurity, defined as “the deep, incapacitating state of not knowing which dangers to confront and which to ignore, i.e., how to get by in the world” (Ibid., p. 345).

This situation leads to the impossibility of behaving as an agent, as «the individual’s energy is consumed meeting immediate needs» (Ibid.). For states, this can lead to identity crises. Mitzen emphasizes that routines do more than provide order; they also constitute identity, and “routines sustain identity; actors become attached to them” (Ibid., p. 347). This attachment makes change difficult, even in the face of material pressure or strategic failure. As she explains, “Individuals like to feel they have agency and become attached to practices that make them feel agentic. Letting go of routines would amount to sacrificing that sense of agency, which is hard to do” (Ibid., p. 348).

De facto statehood and ontological security

As defined in our introduction, de facto states are peculiar entities that are not able to exist and navigate in the international system the same way states do. These definitional features can both be analyzed using ontological security and challenge some of its assumptions. According to Grzybowski (2021), the ontological security framework suffers from the assumption that the studied actors are states in the traditional sense. To him, statehood can be understood as an «exclusive type of subjectivity that constructs a particular community and territory as a corporate person and delineated space, at the expense of all others.» (Ibid., p. 505).

Therefore, nonrecognition can unveil what Grzybowski calls the «fundamental ontological security provided by state subjectivity» (Ibid.). In other words, looking at de facto states reveals some sort of ontological security that is given by state subjectivity, which de facto states do not benefit from. Moreover, states are seeking this fundamental ontological security given by recognition, as it confirms them as states, and state subjectivity is the basic level upon which international relations and routines take place (Grzybowski, 2021).

De facto states are facing an unusual existential threat due to their contested status, and this pushes them to align their physical security concerns (as they are not protected under international law and often in conflict with the parent state) with ontological security ones, their desire for recognition (Ibid.). Their ontological security concerns unfold in two directions: recognition and confirmation of their national identity (Ibid.). Due to this unsafe status, de facto states often try to look like and behave as states even without being directly threatened in terms of physical security (Ibid.).

Additionally, Grzybowski (Ibid.) adds that de facto states pose a meta-security dilemma to third states that intervene in resolving conflicts, implying competing state projects. He describes the meta-security dilemma as follows: «In addressing the security concerns of supposed de facto states—by acknowledging them as actors, granting them support, or, in the extreme case, recognizing them as sovereign states—these entities can be reassured, but only at the cost of rendering their parent states fundamentally insecure.» (Ibid., p. 515).

Narratives as a way to obtain ontological security

According to Eberle and Handl (2018), states seek ontological security through narratives, seen as stories about the past and the future. These narratives are a way for states to «answer questions about doing, acting, and being,» which, by maintaining narratives about the self, provides ontological security (Ibid., p. 44). On top of that, Eberle and Handl (Ibid.) add that narratives about the self are also linked to representations of others and “obtain ontological security by identifying with something or someone” by embedding their narratives in a shared vision of international order. Eberle and Handl (Ibid.) developed a model that consists of three layers of narratives—self, relations with significant others, and international order—which help to show how states seek ontological security (Ibid.). The former shows how «identity of the self is constituted and reinforced intersubjectively by narratively anchoring the state-self in relation to other states—friends, enemies, or rivals» (Ibid., p.45). while the third layer focuses on how identity is related to the international order.

Therefore, we expect to find that allowing the development of narrative about the self, significant others, and the broader international community, Taiwan’s relationship with Somaliland allows the former to acquire ontological security. Thus, it does justify, on Taiwan’s side, the maintenance of a relationship with Somaliland, an entity that is not able to provide physical security to Taiwan.

Methodology

Research design

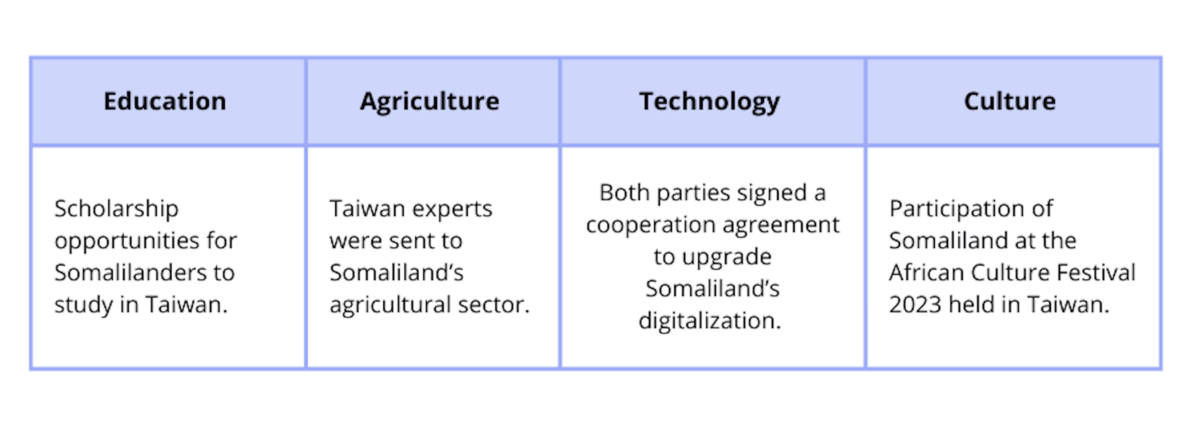

Our research paper will be based on a single case study. We chose the relationship between Taiwan and Somaliland, as they are both fitting our definition of de facto states and do have a more than four-year-long official bilateral relationship. As we indicated, entering the definitional debate on de facto statehood is not the aim of this paper, and our conceptualization is based on Pegg et al.’s definition of de facto states. Scott Pegg (1998) et al. consider Somaliland and Taiwan de facto states. We chose the case of Taiwan and Somaliland, as they reciprocally established representative offices in 2020—purposefully not labeled as embassies—and subsequently developed cooperation across several policy areas (Atimniraye Nyelade, 2024). As summarized in Table 2 in the Figures and Tables section, Somaliland is primarily a recipient of Taiwan’s initiatives.

Method and data collection

Here, we will briefly describe the type of data that will be collected and the method that will be used to collect it. This paper will employ a thematic narrative analysis to examine how Taiwan constructs its relationship with Somaliland in a way that affirms national identity and pursues ontological security. Our analysis will be grounded in Catherine Kohler Riessman’s typology of narrative, which includes thematic, structural, and visual analysis and dialogic/performance (Riessman, 2008; Šalkutė, 2016). We chose the thematic approach, which focuses on the content of the narratives (Ibid.). This will lead us to identify patterns related to identity and ontological security in Taiwan’s official discourse regarding its bilateral relations with Somaliland. We will look at the three dimensions of Eberle and Handl’s model (Eberle & Handl, 2018) mentioned above. As we seek to determine how Taiwan constructs its relationship with Somaliland as a means of affirming national identity in its quest for ontological security, we will be analyzing Taiwan’s official sources in order to identify the above-mentioned narratives. This study’s data mainly consists of textual sources such as government-based communications on the matter, press releases from official websites, and tweets from the Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland and Taiwan MFA’s X accounts. To facilitate our search, we used the keyword “Somaliland” on the representative office’s website and X account, as many statements unrelated to the Taiwan-Somaliland relationship are published daily.

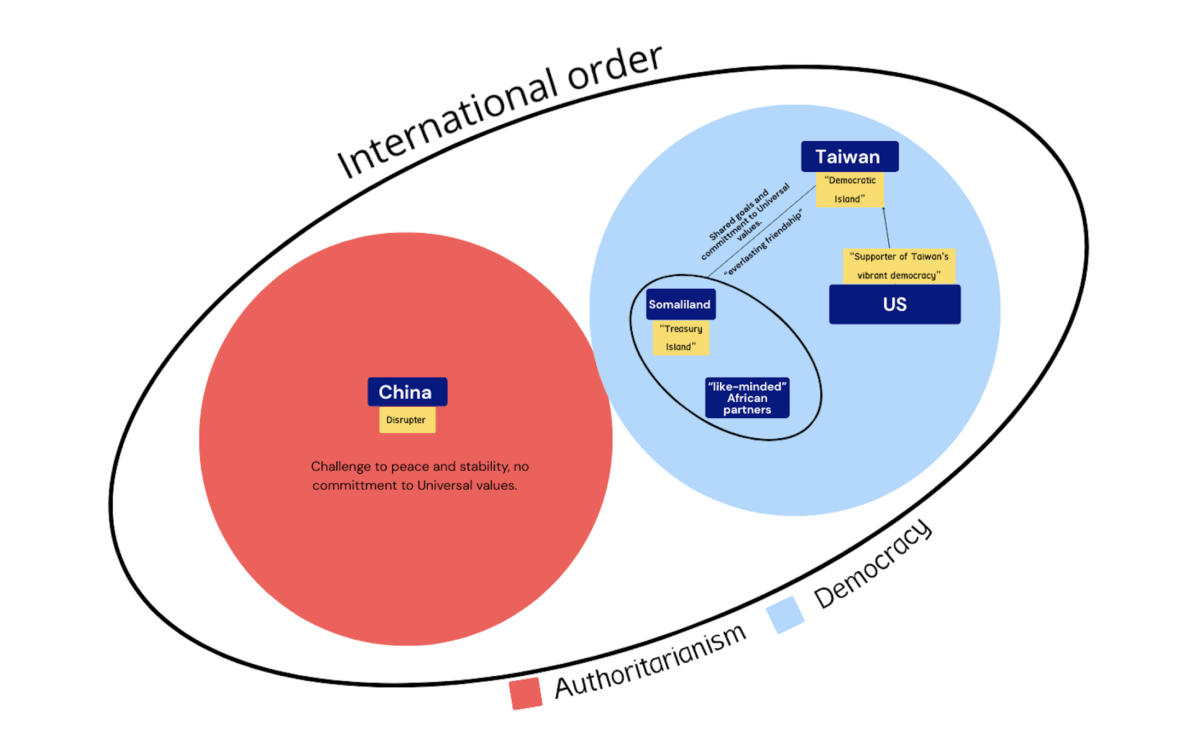

In the following three sections, we will be examining the construction of Taiwan’s narrative using Eberle and Handl’s model (2018). The first part of our analysis will focus on the narrative relative to significant others (Somaliland, China, and the US). In our second part, we will discuss how these narratives are articulated by Taiwan to reinforce its democratic status and its legitimacy in the international system.

Relations with significant others

As mentioned above, Eberle and Handl (2018, p. 45) consider that the identity of the self is consistently «constituted and reinforced intersubjectively by narratively anchoring the state-self in relation to other states—friends, enemies, or rivals.» Against the background of the collected data, we were able to identify three significant others in Taiwan’s narratives. On the one hand, Somaliland is consistently described as a partner that shares the same goal as Taiwan. On the other hand, the collected data shows that China is framed as a disruptive actor, a threat to Taiwan. Less significantly but worth mentioning, the United States is framed as a partner in Taiwan’s democratic enterprise.

Taiwan’s relationship with Somaliland: a way to routinize relationships with like-minded partners

The collected data have shown that Somaliland is pictured as a friend in Taiwan’s grand narratives on significant others, which reinforces Taiwan’s democratic self, discussed later. One could start from the announcement of the installation of a formal relationship between Taiwan and Somaliland, published by the Taiwanese MFA in July 2020. It first states the existence of a «shared commitment to common values of freedom, democracy, justice, and the rule of law.»2 It describes the shift from «cordial»3 relations to «friendly»4 ties. Taiwan places itself as an experienced actor in the domain of international cooperation, which Somaliland can benefit from. It also places Taiwan as a supportive actor in Somaliland’s «efforts to advance democracy and freedom.»5

One of the most important components of the Taiwanese narratives on Somaliland is the inclusion of the latter in the continuity of Taiwan’s view of democracy and international cooperation. Somaliland is, in the analyzed statements, a means and a way for Taiwan to reinforce its narrative about the democratic self. For Taiwan, «peace and stability are the fundamental elements for cooperation»6, and Somaliland is described as a model for that matter. In relation to China (Taiwanese narratives about China are discussed below), Somaliland is pictured as being together with Taiwan, «at the right side of history»7. By this, it is meant that Somaliland shares common values with Taiwan, which the latter «promises to make every effort to defend.»8 The following quote sums up this depiction of Somaliland as committed to the same values as Taiwan against China.

«Somaliland will stand with Taiwan and ask China to let every country choose their way of life and respect their political rights.»9

In this sense, the Taiwanese representative in Somaliland’s speech in the context of the celebration of the 113th Taiwanese National Day in Hargeisa is crucial. In fact, this statement is aimed at reminding the readers and the audience of the importance and aims of this bilateral relationship. It first refers to the invitation of Somaliland’s official to observe the 2024 presidential elections and subsequently to Lai Ching-te’s inauguration ceremony.10 This resonates with the Taiwanese narrative on democracy. Furthermore, the representative’s speech aims to show how committed Taiwan is to exporting these values to allies:

«In September 2024, Taiwan committed $2 million to support Somaliland’s 2024 presidential and party elections. These supports showed Taiwan’s democratic empowerment for Somaliland.»11

If Taiwan’s officials are insisting on the centrality of shared democratic values that are both pictured as central in their identity, other more pragmatic areas of cooperation are mentioned as it encompasses other «prioritized areas such as healthcare, education, agriculture, ICT, security, oil drilling, critical minerals exploration, fishery, humanitarian assistance, etc.»12

More importantly, this relationship is described as a way for Taiwan to think about the future, including Somaliland, allowing Taiwan to overcome uncertainty.

«We will build links with the world through our warm power and resilience and cooperate with Somaliland and other like-minded partners in Africa for a better future.»13

This emphasis on the long term by Taiwanese officials can also be found in other statements, such as Allen Lou’s speech at the Taiwan Security Scholarship ceremony that took place in 2025:

«In closing, I wish for the everlasting friendship between our two nations! I wish you all the best of health and success. Thank you. Insha Allah»14

China as a disruptive actor

In the analyzed documents, China is framed as a disruptive actor that poses a threat to peace, stability, and the international order. In two of the analyzed statements published by the Taiwanese representative in Hargeisa—on the dispatch of a Taiwanese medical mission to Somaliland and on the 2nd anniversary of the establishment of representative offices—China is framed this way:

«In the time that China is still conducting the live-fire drills around Taiwan waters, which are provocative actions to challenge the international order and disrupt peace and stability in the region.»15

This quotation comes from the first statement that was published by the Taiwanese office in Hargeisa on the 8th of August. If it is aimed at communicating the advancements of Taiwan’s health cooperation with Somaliland after the treaty was signed in 2021, it brings up military exercises organized by China, which took place around the island from the 4th to the 7th of August 202216. As opposed to the discourse about the self, where Taiwan pictured itself as a peaceful actor able to provide stability to the international order, China is here depicted as a threat to both. In the following quotation, China is opposed to Taiwan in the way it acts on the international scene.

«Weapons cannot increase human welfare, but PEACE does; HEALTHCARE also does.»17

By describing China this way, Taiwan reinforces its narrative about the self. The weapons used by China in the context of its military exercises, pictured by Taiwan as a threat to its security, are here opposed to the way the latter cooperates with Somaliland. In the second statement, which is aimed at celebrating the Taiwan Scholarship awarding ceremony that took place on August 17th—the day of the second anniversary of the establishment of representative offices—in Hargeisa, China’s military exercises are brought up the exact same way.

«Taiwan firmly believes that ‘weapons cannot increase human welfare, but PEACE does, and EDUCATION also does.»18

The USA as Taiwan’s supporter

Unsurprisingly, the USA is pictured as a strong supporter of Taiwan’s model. In the statement on medical cooperation published on the 8th of August 2022, analyzed above, Nancy Pelosi’s visit is thanked and depicted as a sign of «unwavering commitment to supporting Taiwan’s vibrant democracy.19 If the analyzed statements focus more on the Taiwan-Somaliland bilateral relationship, this «unwavering»20 support from the US comes here as a confirmation of the Taiwanese democratic identity pictured in the narratives on the self.

The self and the international system

In this part, we aim to show how the analyzed data allows Taiwan to deploy narratives about the self and, more broadly, on the international system.

Narratives on the self

As it was reflected earlier, Taiwan’s relationship with Somaliland is included in the former in its broader narrative on the democratic self. This commitment to democratic values on the domestic scene is then presented as a basis for its peculiar model of cooperation, which is often contrasted with China’s mode of engaging with the Horn of Africa. This allows Taiwan to position itself as a responsible member of the international community.

A salient example of this can be found in the speech given on the 10th of October 2024 by the Taiwanese representative to Somaliland. In the retranscription of this speech, Allen Chenhwa Lou states that the January 2024 elections, which brought Lai Ching-te as president, are described as «fair and successful»21. A short excerpt of the latter inauguration speech was then quoted by the representative. Democracy is mentioned among peace and prosperity as a part of Taiwan’s national roadmap. More than that, Taiwanese democracy is described as having arrived in its «glorious era»22.

Moving away from these narratives, the characterization of Taiwan as a democracy on the domestic level and the statements displayed the importance of what is being labeled as the «Taiwan model of International Cooperation»23, which is described as being based on mutually beneficial goals and democratic values. Here, we can take the example of the awarding ceremony of Taiwan Government Scholarships to students in Somaliland in August 2022. The aim of these grants is explicitly labeled as a way for these students to «make great contributions to Somaliland after finishing studies in Taiwan»24 and as the «testimony of the Taiwan Model of cooperation»25.

Furthermore, in the case of a speech given in the context of the Maternal and Infant Health Care Improvement Project, the Taiwan Model of assistance is again evoked:

«The Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland tries to integrate the ongoing cooperation to maximize the cooperation effect to benefit the Somaliland people directly and without leaving any “debt traps.” That is the Taiwan-model cooperation in Somaliland.»26

If this model is presented as directed to Somaliland’s growth, it seems that the content and specificity of this model of assistance are not excessively detailed in these documents. On the contrary, it is way more clearly specified that this Taiwanese model comes as an opposition to China’s way of interacting with its African partners by evoking the risk of debt traps. This model of cooperation between Taiwan and Somaliland is also presented as something that can be used to gather further support among African countries, which are expected to «further support ‘Let Taiwan help’»27.

Lastly, an important aspect of Taiwanese narratives that can be found when the Somaliland-Taiwan relationship is evoked is about justifying the latter’s very existence. In fact, a statement from March 2025 reasserts the legitimacy of Taiwan’s existence and legitimacy:

«Neither Taiwan nor China is subordinate to the other, and China has never governed Taiwan for a second. We strongly refute China’s false claims of territorial sovereignty that completely ignore the fundamental truth.»28

Narratives on the International Order

Lastly, in relation to the presented democratic characteristics and a specific model of cooperation, Taiwanese narratives do spend time framing themselves as a responsible member of the international community regarding global challenges. For instance, on December 4, 2022, Taiwan and Somaliland signed an Agreement on the Dispatch of Volunteers with the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Somaliland. If this agreement seems anecdotal, it is described as a way for Taiwan to tackle global challenges such as the protection of biodiversity. Further in the speech, the statement asserts that:

«As a responsible member of the international community, Taiwan has complied with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora for many years.»29

It is worth mentioning that Taiwan is not able to be a part of this convention due to its de facto statehood but still portrays itself as a model that is committed to protecting biodiversity.

Surprisingly enough, narratives along the lines of stigmatization in the international system weren’t common in the studied data. However, concerning climate change, the inability to «fully engage the formal dialogue of climate actions»30 is evoked in Taiwanese narratives. As was the case with its compliance with the norms of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Taiwanese representatives highlighted that the willingness of the highland to act within multilateral frameworks clashes with its inability to be fully inserted in these political platforms reserved for states. In 2023, the representative of Taiwan to Somaliland regarding the COP28 declared that the very fact that Taiwan, as a central component, was barred from participating in the conferences constitutes an injustice. They notably added that “Denying Taiwan is to Deny Global Climate Reforms”31.

In the same way, we would have expected more direct references to Somaliland’s widespread nonrecognition; only support of their relationship is evoked.

Summary of the findings and interconnections of the narratives

In this section, Figure 1 in the Figures and Tables section synthesizes the three-layered narrative model applied to our case and illustrates how narratives about the self and significant others are interconnected.

First, it seems that Taiwan sees itself as on the «right side of history»32 in these three layers of discourses. The analysis of these statements and discourses showed that Taiwan divides the international community into two incompatible blocks. The first sphere includes democratic countries. At the significant other level, the US is welcomed as it supports Taiwan’s democracy and existence. And Taiwan describes its partnerships in the region (including Somaliland) as a way to strengthen shared values. This coincides with narratives about the self that acknowledge and praise democratic values, which even influence the way it cooperates with Somaliland. The second sphere includes China and potentially its allies (even though they are not mentioned in the studied data). Unsurprisingly, China is described as a challenge to peace, stability, and universal values praised by the democracies and pictured as a threat to the very existence of Taiwan.

Conclusion

Against this background, we can now assess what our analysis can give as answers to our research question: Why do de facto states, despite their limited capacity to provide physical security, pursue bilateral relations? Our analysis of the data has shown that by pursuing bilateral relations, de facto states, as Taiwan did, seek ontological security through the deployment of narratives based on their relationship with their peer. In our case, we did expect more direct references to the absence of widespread recognition and stigmatization in the international community (which we touched upon a bit). We still argue that these bilateral relationships between de facto states allow them to develop fixed views of what they are, who their friends and enemies are, and how they can act in the international system. Lastly, further studies could look at discourses on the two sides of the relationships, as well as compare narratives in de facto bilateral couples. This case study was insightful in the sense that Taiwan’s relationship with Somaliland, which cannot guarantee its physical security, enabled the former to deploy narratives as a way to seek ontological security. However, this has not been considered in the context of this course due to the word limit. One last option for further study is that we could have also looked at Taiwanese statements in the context of bilateral relations with African countries for a comparative study.

Figures and Tables

Table 1. Criteria for de facto statehood based on Pegg’s definition (work of the author).

Table 2. Overview of Taiwan–Somaliland cooperation initiatives, 2020–2024 (work of the author).

Figure 1. Synthesis of Taiwan’s narratives about the self, significant others, and the international order (work of the author).

Notes

Bibliography

Atimniraye Nyelade, R. (2024, June 27). Strategic diplomacy beyond recognition: Taiwan and Somaliland’s people-centered relations in the global arena. Kujenga Amani. https://kujenga-amani.ssrc.org/2024/06/27/strategic-diplomacy-beyond-recognition-taiwan-and-somalilands-people-centered-relations-in-the-global-arena/

Bastek, R. W. (2019). De facto state–patron state relations in two-level game theory: A case study on de facto states in Croatia and Bosnia during the Yugoslav Wars (Master’s thesis, University of Tartu, Johann Skytte Institute of Political Science). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/223010039.pdf

Berg, E., & Vits, K. (2018). Quest for survival and recognition: Insights into the foreign policy endeavors of the post-Soviet de facto states. Ethnopolitics, 17(4), 390–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.1495359

Caspersen, N. F. (2018). Recognition, status quo, or reintegration: Engagement with de facto states. Ethnopolitics, 17(4), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.1495360

Eberle, J., & Handl, V. (2018). Ontological security, civilian power, and German foreign policy toward Russia. Foreign Policy Analysis, 16(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/ory012

Florea, A. (2017). De facto states: Survival and disappearance (1945–2011). International Studies Quarterly, 61(2), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw049

Grzybowski, J. (2021). Separatists, state subjectivity, and fundamental ontological (in)security in international relations. International Relations, 36(3), 456–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/00471178211045619

Ker-Lindsay, J. (2018). The stigmatization of de facto states: Disapproval and ‘engagement without recognition.’ Ethnopolitics, 17(5), 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.xxxxxx

Kosienkowski, M. (2022). Four problems of de facto state studies: A Central European perspective. Polish Political Science Yearbook, 51, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.15804/ppsy202244

Kursani, S. (2020). Reconsidering the contested state in post-1945 international relations: An ontological approach. International Studies Review, 23(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viaa073

Mitzen, J. (2006). Ontological security in world politics: State identity and the security dilemma. European Journal of International Relations, 12(3), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066106067346

Pegg, S. (1998). De facto states in the international system. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/46433/WP21.pdf

Riessman, C. K. (2023, April 7). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications Ltd. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/narrative-methods-for-the-human-sciences/book226139

Šalkutė, B. (2016). Secure or otherwise: Lithuania’s ontological security after EU and NATO accession. DSpace.ut.ee. https://dspace.ut.ee/items/c4cf3e9c-29cf-47ef-a9d3-c9811e237d90

Toomla, R. (2016). Charting informal engagement between de facto states: A quantitative analysis. Space and Polity, 20(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2016.1243037

Visoka, G. (2022). Statehood and recognition in world politics: Towards a critical research agenda. Cooperation and Conflict, 57(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367211007876

Sources (Data collection)

Davidson, H., & Ni, V. (2022, August 4). China to begin series of unprecedented live-fire drills off Taiwan coast. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/03/china-to-begin-series-unprecedented-live-fire-drills-off-coast-of-taiwan

Library Guides. (n.d.). APA 7th referencing: Social media. Retrieved May 1, 2025, from https://libraryguides.vu.edu.au/apa-referencing/7SocialMedia

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). (n.d.). Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). https://en.mofa.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=1328&s=93672

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-a). Taiwan signs the Energy and Mineral Resources Cooperation Agreement with Somaliland. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/642.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-b). Taiwan dispatches the medical mission to Somaliland. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/695.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-c). “Building peace through democracy and building dreams through education”: Awards 26 Somaliland students Taiwan Government Scholarships. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/700.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-d). Taiwan hands over the fund of maternal and infant health care improvement project to Somaliland. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/755.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-e). Save the cheetahs from extinction: Taiwan signed agreement on dispatch of volunteers with Cheetah Conservation Fund. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/791.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-f). Taiwan’s cooperation in Africa for a Net-Zero future. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/929.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-g). Taiwan celebrates 113th National Day in the Republic of Somaliland. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/1100.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-h). Amb. Allen Lou’s remarks at Taiwan Security Scholarship awarding ceremony on 8th March, 2025. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/1152.html

Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. (n.d.-i). Statement from Taiwan Representative Office in the Republic of Somaliland. https://www.roc-taiwan.org/smd_en/post/1148.html

Taiwan In Somaliland [@Taiwan_SLD]. (2025, January 15). Congratulations to Amb. Mohammed Omar Haji Mohamoud for his new appointment as the advisor of international affairs to the H.E. President Abdirahman Abdullahi [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/Taiwan_SLD/status/1879477414075699323

外交部 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ROC (Taiwan) [@MOFA_Taiwan]. (2020, July 1). We’ve signed an agreement with #Somaliland to establish good relations [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/MOFA_Taiwan/status/1278229665883148288

外交部 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ROC (Taiwan) [@MOFA_Taiwan]. (2021, August 17). On Aug. 17, 2020, a new chapter in history was written: Opening of #Taiwan Representative Office in #Somaliland [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/MOFA_Taiwan/status/1427587026216357891

外交部 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ROC (Taiwan) [@MOFA_Taiwan]. (2022, February 22). Great to exchange views with the ministerial delegation led by @DrEssaKayd [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/MOFA_Taiwan/status/1491388762064318467

外交部 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ROC (Taiwan). [@MOFA_Taiwan]. (2020, July 1). We’ve signed an agreement with #Somaliland to establish good relations. [Images attached] [Tweet]. X.

Further Reading on E-International Relations