Borders have long been considered as the defining markers of the international order, stabilizing the relationship between sovereignty, territory, and authority. The “Westphalian model” of international relations, anchored in the Peace of Westphalia (1648), rested upon the principle that political authority was bounded and mutually recognized across territorial lines (Krasner 1999; Agnew 1994). Yet, in the early 21st century, this idea of borders as static territorial lines is increasingly insufficient to capture the complexities of global politics. Borders have become dispersed, deterritorialized, and enacted in multiple sites and practices beyond the geopolitical map (Balibar 2002; Sassen 2006). This dispersal generates not only novel governance mechanisms but also new modalities of violence—both visible and invisible—through which inclusion and exclusion are performed.

The framing of “borders as violence” extends Charles Tilly’s insight that “[…] and state-making is organized crime” into the realm of bordering practices (Tilly 1985). Borders do not merely demarcate; they regulate, discipline, and often harm. Violence occurs in at least three interrelated forms: direct violence at the border (such as pushbacks and detention), structural violence embedded in the legal-administrative regimes of mobility (such as visa restrictions or sanctions), and symbolic violence that stigmatizes and delegitimizes certain groups (Galtung 1969; Bourdieu 1991; Vaughan-Williams 2009). Taken together, these forms underscore that bordering is not a neutral act of spatial management but a political practice that legitimizes exclusion and produces hierarchies of belonging.

The emergence of what may be called a post-Westphalian order complicates traditional assumptions of international relations theory. Whereas Westphalian sovereignty emphasized territorial integrity and sovereignty, contemporary bordering practices are enacted by a multiplicity of actors—states, corporations, international organizations, and even algorithms (Amoore 2006; Cowen 2014). These practices stretch borders beyond physical lines: from biometric databases in airports to financial de-risking measures in global banking, from humanitarian corridors in conflict zones to data infrastructures that filter access to digital spaces (Mezzadra and Neilson 2013; Larkin 2013). The result is that borders migrate into everyday life, often distant from the territorial frontier, while reproducing forms of violence that remain underexplored in mainstream scholarship.

Critical border studies have highlighted the mobility of borders and the idea of “borderscapes” to capture their shifting nature (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr 2007; Brambilla 2015). Yet these concepts risk underestimating the changing nature of violence in a post-Westphalian context, where bordering practices extend through infrastructures, legal norms, and symbolic orders as much as through territorial checkpoints. The inadequacy of existing categories raises an urgent question: is international relations as a discipline, with its statist biases and reliance on sovereignty as a core category, theoretically equipped to grasp these transformations? While constructivist and critical approaches emphasize the social construction of borders, they often fail to account for the material infrastructures and technological mediations that render violence diffuse but palpable (Sassen 2006; Aradau and Blanke 2017).

Rethinking Borders in a Post-Westphalian Context

The notion of a post-Westphalian order has become indispensable in debates on sovereignty and international politics. While the Peace of Westphalia established the enduring principle of territorial sovereignty as the foundation of modern statehood, contemporary transformations reveal that borders now function less as rigid lines and more as dispersed regimes of control (Agnew 1994; Krasner 1999). The Westphalian imaginary assumed that authority was concurrent with territory and that borders merely reflected the geographical limits of political jurisdiction. By contrast, in today’s global order, borders operate through infrastructures, technologies, and transnational practices that extend far beyond physical frontiers, reconfiguring sovereignty as a fragmented and often extraterritorial process (Sassen 2006; Walters 2002).

This shift challenges one of the most basic ontological assumptions of international relations: that borders are fixed and stable. Borders are now enacted in biometric databases, refugee camps, offshore detention sites, airline check-in counters, and even humanitarian corridors, revealing their mobility and multiplicity (Mountz 2011; Mezzadra and Neilson 2013). The concept of “bordering” as an active practice rather than a static line captures this transformation, emphasizing that sovereignty is reproduced through everyday acts of regulation and control across dispersed sites (Paasi 1996; Newman 2006). In this sense, borders are less about where the state ends and more about how power is exercised in shaping inclusion and exclusion at a distance.

Critical border studies have sought to capture this dynamism through the language of “borderscapes”, highlighting the fluidity of border practices and the way they intersect with mobility, migration, and identity (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr 2007; Brambilla 2015). The notion of borderscapes has been invaluable in problematizing the naturalization of borders and in showing how borders are lived, negotiated, and contested. Yet, as borders increasingly manifest in digital infrastructures, financial regulations, and humanitarian regimes, the concept may be insufficient to grasp the intensifying forms of violence that accompany them. The emphasis on fluidity sometimes obscures the coercive and exclusionary dimensions of contemporary bordering, which rely on the systematic production of insecurity and marginalization (Vaughan-Williams 2009; De Genova 2013).

The inadequacy of borderscapes becomes clearer when violence is placed at the centre of analysis. Following Tilly’s claim that state-making is organized crime (Tilly 1985), borders themselves should be understood as producing violence in three interrelated forms: direct, structural, and symbolic (Galtung 1969; Bourdieu 1991). Border practices not only inflict bodily harm—through pushbacks, or the use of force—but also reproduce structural inequalities, such as the denial of mobility rights or access to resources. At the same time, they inscribe symbolic hierarchies, labelling certain groups as “illegals”, “threats,” or “undeserving” (Butler 2009; Mbembe 2003). This triadic framework exposes the limitations of approaches that stress only mobility or fluidity without addressing the violence embedded in bordering itself.

The implications for international relations are significant. Traditional realist or liberal theories, rooted in the Westphalian template, remain ill-suited to explain why borders now extend into logistical hubs, data infrastructures, and humanitarian spaces. Critical approaches highlight the social construction of borders but often underplay the material infrastructures and technologies that stabilize them (Amoore 2006; Aradau and Blanke 2017). Postcolonial and feminist interventions foreground the unequal and gendered experiences of bordering, yet these insights have rarely been integrated into the core explanatory frameworks of IR (Tickner 2018; Acharya 2014). As a result, the discipline risks treating these transformations as anomalies rather than as signs of a deeper reconfiguration of political order.

To rethink borders in a post-Westphalian context thus requires more than descriptive categories like borderscapes. It requires acknowledging borders as hybrid assemblages where discursive, material, and symbolic processes converge. These assemblages produce violence not at the margins alone but within the very circuits of global governance, finance, and humanitarianism. Recognizing this hybridity allows us to see that borders are neither simply social constructs nor purely physical demarcations but are simultaneously both—and always instruments of power and exclusion. In this sense, the study of borders offers a window into the broader transformation of world politics, one where sovereignty, order, and violence are constantly renegotiated across shifting terrains.

A Typology of Bordered Violence: Transformations in Bordering Practices Across Scales

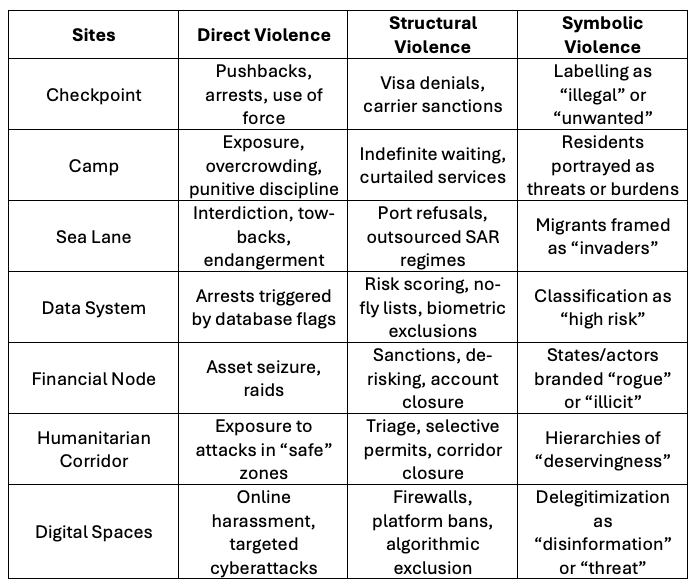

Understanding borders as violence requires a systematic framework that captures both the modalities of harm and the diverse sites where they are enacted. Drawing on Johan Galtung’s (1969) classic distinction between direct and structural violence, alongside Pierre Bourdieu’s (1991) theorization of symbolic domination, this article proposes a triadic typology: direct violence (bodily harm and coercion), structural violence (systematic deprivation via rules and infrastructures), and symbolic violence (discursive classifications that normalize exclusion). This typology is especially pertinent in a post-Westphalian order where borders migrate into camps, digital databases, financial infrastructures, and humanitarian corridors (Sassen 2006; Walters 2002; Mezzadra and Neilson 2013).

What emerges from this mapping is not only the diversification of border sites but also the intensification of violence through infrastructural mediation. Unlike the traditional frontier, these sites operate through a layering of modalities that blur the line between coercion and administration. For instance, in the digital domain, exclusion rarely appears as overt force but rather as algorithmic invisibility—the quiet erasure of voices through shadow-banning, deplatforming, or classification as “foreign influence” (Aradau and Blanke 2017; Lyon 2014). Such practices produce structural harm by denying access to public discourse while simultaneously embedding symbolic hierarchies about who counts as legitimate knowledge producer or political actor.

Another insight is that modalities often overlap and cascade across sites. A biometric refusal in a data system may trigger detention at a checkpoint; a financial sanction can amplify deprivation in camps; the stigmatization of “illegals” on sea lanes may be reinforced through hostile narratives circulating in digital space. This interdependence highlights that bordered violence is not site-specific but systemic, forming what Mezzadra and Neilson (2013) call a “multiplication of labour and control” across global networks.

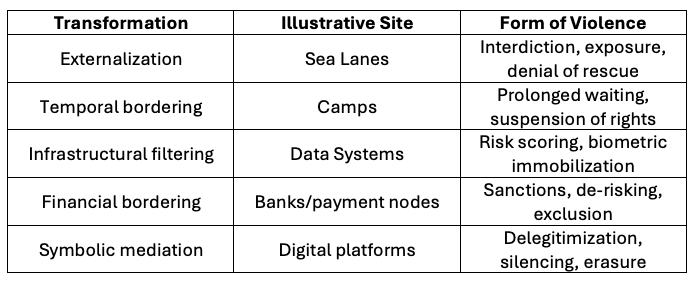

The transformation of borders in the post-Westphalian order is most visible in the ways bordering practices have migrated from territorial frontiers into infrastructures, institutions, and everyday spaces. Rather than acting as singular lines of demarcation, borders now operate through dispersed mechanisms that regulate mobility and belonging at multiple scales. This transformation is not only spatial but also qualitative: violence once concentrated at the border fence now travels through data flows, financial circuits, and humanitarian spaces. What binds these sites together is the interplay of direct, structural, and symbolic violence, which together constitute the architecture of exclusion (Galtung 1969; Bourdieu 1991; Sassen 2006).

A key feature of this transformation is externalization, whereby states displace coercion away from their territorial limits. Maritime interdictions, offshore processing facilities, and delegated search-and-rescue operations exemplify how borders are projected outward, producing spaces of indeterminate sovereignty where accountability is blurred (Walters 2002; Vaughan-Williams 2009). At the same time, bordering extends inward and downward through infrastructural logics. Camps, waiting zones, and biometric databases normalize long-term suspension of rights, embodying what Mountz (2011) calls “temporal bordering”. Here violence is less spectacular but no less effective, eroding life chances through waiting, rationing, and constant surveillance.

A parallel transformation occurs in domains not traditionally associated with borders. Financial regulations—sanctions, de-risking policies, compliance regimes—transform banking halls and payment systems into chokepoints of mobility. By enlisting private actors in enforcement, these mechanisms multiply the reach of state power while masking political violence as technical compliance (Sassen 2006). Similarly, digital platforms now act as border sites. Algorithms filter speech, firewalls exclude populations, and online identities are recoded as “foreign influence” or “disinformation” (Aradau and Blanke 2017). Though rarely involving direct coercion, such practices immobilize voices and shape the symbolic order of who counts as a legitimate actor.

These transformations do not exist in isolation; they form cascades of violence that connect multiple sites. A biometric “hit” in a data system can trigger denial of boarding at an airport, eventual confinement in a camp, and intensified deprivation if sanctions cut off supplies. Borders thus operate less as checkpoints and more as networks of filtering, where harm is distributed across scales of governance and infrastructure.

Are Borders Still “Social Constructs”? Reframing Ontology

The question of whether borders are merely social constructs or enduring physical realities has long animated debates in international relations and border studies. Early constructivist interventions emphasized that borders are historically contingent products of political negotiation and discursive framing, rather than natural or immutable features of world politics (Paasi 1996; Newman 2006). From this perspective, borders are practices of meaning-making, anchored in narratives of sovereignty, identity, and order. Yet to describe them solely as constructs risks underestimating their materiality. Fences, biometric gates, detention centres, and digital firewalls demonstrate that borders are inscribed in infrastructures and technologies that exert coercive force in everyday life (Sassen 2006; Larkin 2013). The challenge, therefore, is not to choose between social or physical but to recognize that borders are hybrid assemblages where discursive classifications and material infrastructures reinforce each other.

This hybridity becomes evident when symbolic categories crystallize into material consequences. The discursive designation of certain migrants as “illegal” or “threatening” legitimizes both the construction of walls and the deployment of algorithmic surveillance systems (De Genova 2013; Amoore 2006). Conversely, material infrastructures themselves shape discourse: biometric databases and data-driven risk scoring embed classificatory logics that normalize exclusion under the guise of technical neutrality (Aradau and Blanke 2017). Such feedback loops demonstrate that borders are performative—producing realities of inclusion and exclusion through both narrative and infrastructure (Butler 2009).

Reframing ontology in this way highlights that borders should be seen neither as purely imagined lines nor as brute material obstacles, but as constructed-material hybrids that are simultaneously symbolic and concrete. This perspective aligns with critical approaches that emphasize assemblages of law, technology, and discourse as constitutive of sovereignty in practice (Mezzadra and Neilson 2013; Vaughan-Williams 2009). By rejecting the binary of “social” versus “physical,” scholars can better grasp how borders exert power in the post-Westphalian order, where the violence of exclusion travels through camps, databases, financial systems, and digital platforms as much as through territorial frontiers.

Can IR Explain This? Taking Stock of Theories

The transformations of borders in the post-Westphalian order pose a direct challenge to international relations as a discipline. For much of its history, IR has relied on the assumption that borders coincide with the territorial limits of sovereign states and that international politics unfolds in the spaces between them. Realism, with its focus on anarchy and state power, continues to see borders primarily as barriers against external threats, instruments of defence, and markers of sovereignty (Waltz 1979). Liberal theories, for their part, treat borders as institutionalized gateways, emphasizing regimes of cooperation that facilitate trade and movement across them (Keohane and Nye 1977). Both approaches remain tied to the Westphalian model, in which borders are fixed lines that enclose political authority. As a result, they struggle to account for borders that operate through dispersed infrastructures, digital technologies, or humanitarian corridors, where violence is enacted without direct reference to territorial defence.

Constructivist approaches make an important contribution by stressing the social construction of borders through norms, identities, and shared meanings (Wendt 1999; Paasi 1996). They are particularly adept at showing how sovereignty and exclusion are legitimized discursively, thereby capturing the symbolic violence of bordering (Bourdieu 1991; Butler 2009). Yet constructivism has often lacked the analytical tools to address the material infrastructures—databases, biometric systems, or sanctions regimes—that stabilize discursive categories and produce harm beyond meaning-making (Sassen 2006; Amoore 2006). Without attention to these infrastructures, constructivist accounts risk remaining at the level of discourse while missing how exclusion is operationalized in practice.

Critical and poststructuralist interventions have attempted to fill this gap. Postcolonial scholars have demonstrated how colonial legacies continue to shape contemporary bordering practices, from racialized mobility regimes to global migration hierarchies (Mbembe 2003; Acharya 2014). Feminist scholars have exposed the gendered dimensions of borders, where practices of care and control intersect in camps, humanitarian corridors, and domestic labour migration (Tickner 2018). These approaches illuminate the unequal and often violent experiences of bordering from below, challenging IR’s statist bias. Yet, despite their critical force, they often remain marginalized within the discipline, treated as “add-ons” rather than integrated into its explanatory canon. The risk is that IR continues to regard the dispersed, infrastructural character of borders as anomalies, rather than as central to the contemporary order.

More recent theoretical developments offer a partial remedy. Practice theory, with its focus on everyday actions and material enactments, provides tools to analyse how bordering is reproduced through mundane routines, from biometric scanning to financial compliance protocols (Adler and Pouliot 2011). Assemblage theory and science and technology studies (STS) approaches extend this insight, showing how sovereignty emerges from heterogeneous networks of law, infrastructure, and technology (Larkin 2013; Mezzadra and Neilson 2013). Meanwhile, the call for a “Global IR” urges the discipline to provincialize its Westphalian assumptions and recognize plural histories, logics, and epistemologies of order (Acharya 2014). Together, these strands move IR toward a framework capable of grasping borders as hybrid assemblages that generate violence across multiple sites.

The task for IR, therefore, is not to abandon its concern with sovereignty and power but to reconceptualize them in light of dispersed practices of bordering. Sovereignty no longer resides solely in the defence of territorial lines; it is also enacted in data infrastructures, financial regulations, and humanitarian regimes. Violence is not confined to war or military coercion but is reproduced through bureaucratic suspension, symbolic delegitimation, and algorithmic filtering. If IR is to remain relevant, it must develop a synthetic, practice-oriented approach that can integrate constructivist sensitivity to meaning, critical attention to inequality, and materialist analyses of infrastructures. Only then can the discipline adequately explain how borders, far from fading, have become central sites of power and violence in the post-Westphalian order.

Methodological Notes: How to Study Bordered Violence

If borders in the post-Westphalian order are no longer confined to territorial lines but operate through dispersed infrastructures and practices, then studying them demands methodological innovation. Traditional approaches in international relations have relied heavily on state-centric data, formal treaties, and security doctrines, which privilege visible manifestations of sovereignty. Yet the violence of contemporary bordering is often diffuse, embedded in mundane procedures and technical systems that elude such datasets. Capturing these dynamics requires a methodological reorientation toward practices, infrastructures, and lived experiences.

One fruitful avenue is the study of border events, moments when the border materializes in practices that can be observed, contested, and recorded (Vaughan-Williams 2009). These events range from maritime interdictions to algorithmic refusals of entry and provide entry points for tracing how violence unfolds across sites. Process tracing can then link the symbolic designation of a migrant as “illegal” to material consequences such as detention or deportation (De Genova 2013). By following these chains of causality, scholars can expose the mechanisms through which symbolic, structural, and direct violence intersect.

Equally crucial is infrastructural ethnography, an approach that investigates the material systems through which sovereignty is exercised (Larkin 2013). Studying biometric enrolment centres, refugee camps, or financial compliance offices reveals how technical routines function as sites of bordering. Ethnography uncovers the everyday enactment of exclusion, highlighting the ways individuals navigate, resist, or negotiate violent structures (Mountz 2011). Such methodologies also foreground the agency of actors beyond the state, including private firms, humanitarian agencies, and algorithm designers, thereby destabilizing IR’s statist bias.

Critical data studies provide another tool, particularly for analysing digital and algorithmic borders. Audit methodologies can interrogate biometric systems, risk-scoring algorithms, and watchlists, evaluating their accuracy, bias, and accountability (Amoore 2006; Aradau and Blanke 2017). These methods illuminate how structural and symbolic violence are encoded into data infrastructures, producing exclusions that are both normalized and obscured by technical language. Linking these insights to IR requires expanding what counts as valid evidence, treating datasets, code, and algorithms as artefacts of global governance.

The comparative and multi-sited approaches are indispensable. Borders now operate as cascades across checkpoints, camps, financial nodes, and digital platforms, so no single site provides a complete picture. Comparative research can reveal patterns of how violence travels between domains, such as when a biometric refusal cascades into financial exclusion or encampment. Methodologically, this means combining qualitative depth with systemic breadth—juxtaposing case studies with mapping exercises that trace networks of bordering across scales (Mezzadra and Neilson 2013).

Therefore, these approaches reposition the study of borders as a practice-centred enterprise. By moving beyond state-centric documents and formal institutions to follow events, infrastructures, data, and cascades, scholars can grasp how violence is embedded in the dispersed routines of global governance. Such methodological pluralism is not a departure from IR but a necessary extension of it, one that allows the discipline to register borders as central sites of power in the post-Westphalian world.

Conclusion

The transformations of borders in the post-Westphalian order compel us to reconsider both the ontology of borders and the theoretical tools available to international relations. Borders are no longer simply lines on maps demarcating sovereign territories but hybrid assemblages that operate across multiple sites—maritime spaces, camps, data infrastructures, financial systems, humanitarian corridors, and digital platforms. These dispersed practices produce violence not only in direct and visible forms but also in structural patterns of deprivation and in symbolic hierarchies that normalize exclusion (Galtung 1969; Bourdieu 1991; Butler 2009). To reduce borders to either social constructs or physical barriers is therefore misleading; they are simultaneously constructed and material, enacted through the interplay of discourse, law, and technology (Sassen 2006; Mezzadra and Neilson 2013).

This reconfiguration challenges the explanatory power of mainstream IR theories. Realism and liberalism, grounded in statist assumptions, remain inadequate to capture the violence embedded in infrastructures and transnational practices. Constructivism has illuminated the discursive dimension of bordering, yet it struggles to address the materiality of infrastructures and technologies that stabilize exclusion. Postcolonial, feminist, and critical interventions have revealed the lived experiences of marginalization, though they remain insufficiently integrated into the discipline’s core canon (Mbembe 2003; Tickner 2018). A practice-oriented, Global IR approach is therefore essential—one that bridges normative analysis, infrastructural ethnography, and systemic comparison, while provincializing Westphalian categories (Acharya 2014; Adler and Pouliot 2011).

The typology of bordered violence proposed here—direct, structural, and symbolic—offers a conceptual tool for analysing how exclusion is enacted across diverse sites. By tracing cascades of harm, such as how a biometric “hit” may lead to detention, encampment, or financial exclusion, scholars can better map the systemic character of bordering in the contemporary order. This approach also illuminates the productive dimension of borders: they not only exclude but also create categories of “deserving” and “undeserving,” “secure” and “threatening,” which in turn legitimize further practices of control.

In sum, borders have not disappeared in a globalized world but have multiplied and diffused, embedding violence in everyday infrastructures and symbolic orders. For IR, the challenge is to register borders as central, not peripheral, to contemporary world politics. Recognizing borders as distributed violence allows scholars to reimagine sovereignty, governance, and order in ways that move beyond the Westphalian template. It also calls for novel global governance mechanisms that address not only territorial disputes but also the dispersed practices of exclusion and marginalization shaping lives across scales. Only by doing so can IR hope to remain theoretically relevant and empirically attuned to the transformations of borders in the twenty-first century.

Figures

TABLE 1. Mapping violence modalities against specific bordering sites.

Note: The table illustrates how each site produces distinct but interrelated forms of harm.

TABLE 2. Border sites and broader systems of exclusion

Note: The table highlights how transformations link sites into broader systems of exclusion.

References

Acharya, Amitav. 2014. Rethinking Power, Institutions and Ideas in World Politics: Whose IR? London: Routledge.

Adler, Emanuel, and Vincent Pouliot. 2011. International Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amoore, Louise. 2006. “Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror.” Political Geography 25 (3): 336–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.02.001.

Aradau, Claudia, and Tobias Blanke. 2017. “Politics of Prediction: Security and the Time/Space of Governmentality in the Age of Big Data.” European Journal of Social Theory 20 (3): 373–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431016667623.

Balibar, Étienne. 2002. Politics and the Other Scene. London: Verso.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited by John B. Thompson. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Brambilla, Chiara. 2015. “Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept.” Geopolitics 20 (1): 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884561.

Butler, Judith. 2009. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso.

Cowen, Deborah. 2014. The Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1180–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.783710.

Galtung, Johan. 1969. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6 (3): 167–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301.

Keohane, Robert O., and Joseph S. Nye. 1977. Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition. Boston: Little, Brown.

Krasner, Stephen D. 1999. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Larkin, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 327–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

Lyon, David. 2014. Surveillance after Snowden. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Mbembe, Achille. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11.

Mezzadra, Sandro, and Brett Neilson. 2013. Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mountz, Alison. 2011. Seeking Asylum: Human Smuggling and Bureaucracy at the Border. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Newman, David. 2006. “The Lines That Continue to Separate Us: Borders in Our ‘Borderless’ World.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (2): 143–61. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132506ph599xx.

Paasi, Anssi. 1996. Territories, Boundaries and Consciousness: The Changing Geographies of the Finnish-Russian Border. Chichester: Wiley.

Rajaram, Prem Kumar, and Carl Grundy-Warr, eds. 2007. Borderscapes: Hidden Geographies and Politics at Territory’s Edge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ruggie, John Gerard. 1993. “Territoriality and Beyond: Problematizing Modernity in International Relations.” International Organization 47 (1): 139–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300004732.

Sassen, Saskia. 2006. Territory, Authority, Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tickner, J. Ann. 2018. “Gendering a Discipline: Some Feminist Methodological Contributions to International Relations.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (3): 607–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy027.

Tilly, Charles. 1985. “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime.” In Bringing the State Back In, edited by Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol, 169–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vaughan-Williams, Nick. 2009. Border Politics: The Limits of Sovereign Power. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Vaughan-Williams, Nick. 2015. Europe’s Border Crisis: Biopolitical Security and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walters, William. 2002. “Deportation, Expulsion, and the International Police of Aliens.” Citizenship Studies 6 (3): 265–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362102022000011612.

Waltz, Kenneth N. 1979. Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Wendt, Alexander. 1999. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00043.

Further Reading on E-International Relations