Crows Are Good at Geometry. Don’t Look So Surprised

Crows can tell the shapes of stars from those of moons and symmetrical quadrilaterals from unsymmetrical ones, new results show

Carrion Crow (Corvus corone).

AGAMI Photo Agency/Alamy Stock Photo

Crows sometimes have a bad rap: they’re said to be loud and disruptive, and myths surrounding the birds tend to link them to death or misfortune. But crows deserve more love and charity, says Andreas Nieder, a neurophysiologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. They not only can be incredibly cute, cuddly and social but also are extremely smart—especially when it comes to geometry, as Nieder has found.

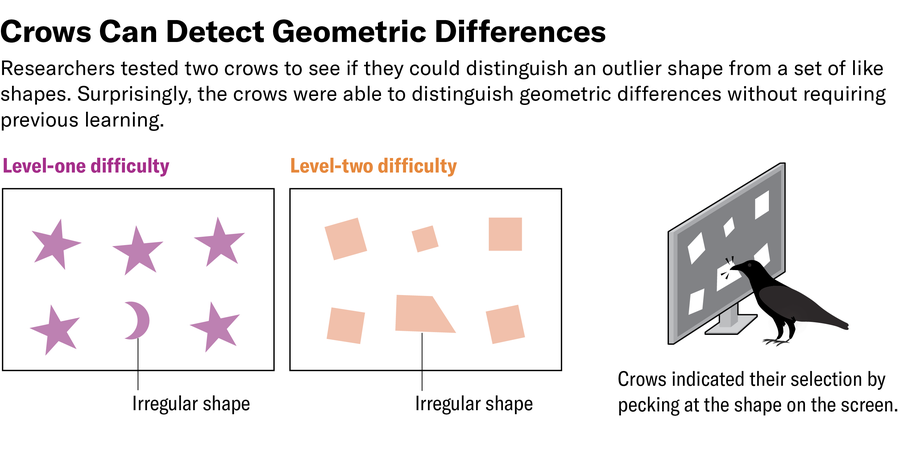

In a paper published on Friday in Science Advances, Nieder and his colleagues report that crows display an impressive aptitude at distinguishing shapes by using geometric irregularities as a cognitive cue. These crows could even discern quite subtle differences. For the experiment, the crows perched in front of a digital screen that, almost like a video game, displayed progressively more complex combinations of shapes. First, the crows were taught to peck at a certain shape for a reward. Then they were presented with that same shape among five others—for example, one star shape placed among five moon shapes—and were rewarded if they correctly picked the “outlier.”

“Initially [the outlier] was very obvious,” Nieder says. But once the crows appeared to have familiarized themselves with how the “game” worked, Nieder and his team introduced more similar quadrilateral shapes to see if the crows would still be able to identify outliers. “And they could tell us, for instance, if they saw a figure that was just not a square, slightly skewed, among all the other squares,” Nieder says. “They really could do this spontaneously [and] discriminate the outlier shapes based on the geometric differences without us needing them to train them additionally.” Even when the researchers stopped rewarding them with treats, the crows continued to peck the outliers.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Telling shapes apart based strictly on geometric properties, such as side lengths or inner angles, is a lot trickier than it sounds, says Giorgio Vallortigara, a neuroscientist at the University of Trento in Italy. Vallortigara, who was not involved in the new study, explains that almost all animals do recognize differences in length or area of surfaces to some extent. But it requires even more cognitive sophistication to identify that, for instance, squares and triangles have different numbers of sides or different inner-angle sizes on flat, two-dimensional surfaces.

“The general view among scientists was that proper geometrical, Euclidean knowledge as applied to objects … was probably limited to humans,” Vallortigara says. Nieder’s work now “is challenging this view—because the crows show a sort of intuitive, strictly perceptual recognition of geometric properties.”

But why are crows good at geometry? The reason is likely evolutionary, scientists say. “I suspect that the origin and the drive for the development of these abilities mainly has to do with spatial orientation,” Vallortigara says. “It could be that, depending on foraging habits or other things, [crows] had more need to develop that [than] other species.”

On the other hand, geometric intelligence is also a key part of recognizing faces, for example, because we use the position of features such as the eyes and mouth to distinguish between individuals. If that’s the case, crows might be using their geometric intelligence for mate selection or individual recognition, Vallortigara says.

Of course, such benefits could easily apply to other animals, and both Nieder and Vallortigara concur that it wouldn’t be surprising if other birds—or any other animal, for that matter—were also capable of similar feats. “All these capabilities, at the end of the day, from a biological point of view, have evolved because they provide a survival advantage or a reproductive advantage,” Nieder says.

These abilities might also have evolved in many different ways. For example, our cerebral cortex, “the site in the brain that is integrating all sorts of information and making us smart and conscious,” didn’t develop in birds, who instead have much simpler arrangements of independent neurons, Nieder explains. But in spite of these genetic differences, “these animals are terribly intelligent—so, obviously, evolution found two different ways of giving rise to behaviorally flexible animals.”

Nieder hopes that future research will reveal what parts of the crow’s brain are responsible for this geometric intelligence. “It is very important that we can work with animals and also can explore these animals. We learn a lot about their brains but also about our brains because we have such fundamental skills that we share with them.”